An ellipse is a disciplined thing. Start with the minor axis—it tells you how the circle tilts in

space. If that line is wrong, your cup or bowl will never sit on the table properly.

Decide your eye level. As you lower your viewpoint, the ellipse opens; as you raise it, the oval

closes. Keep the front and back arcs related—no pinching, no points.

When painting, let values carry the form. Use sharp edges only where necessary and keep most

transitions gentle so the cylinder feels round.

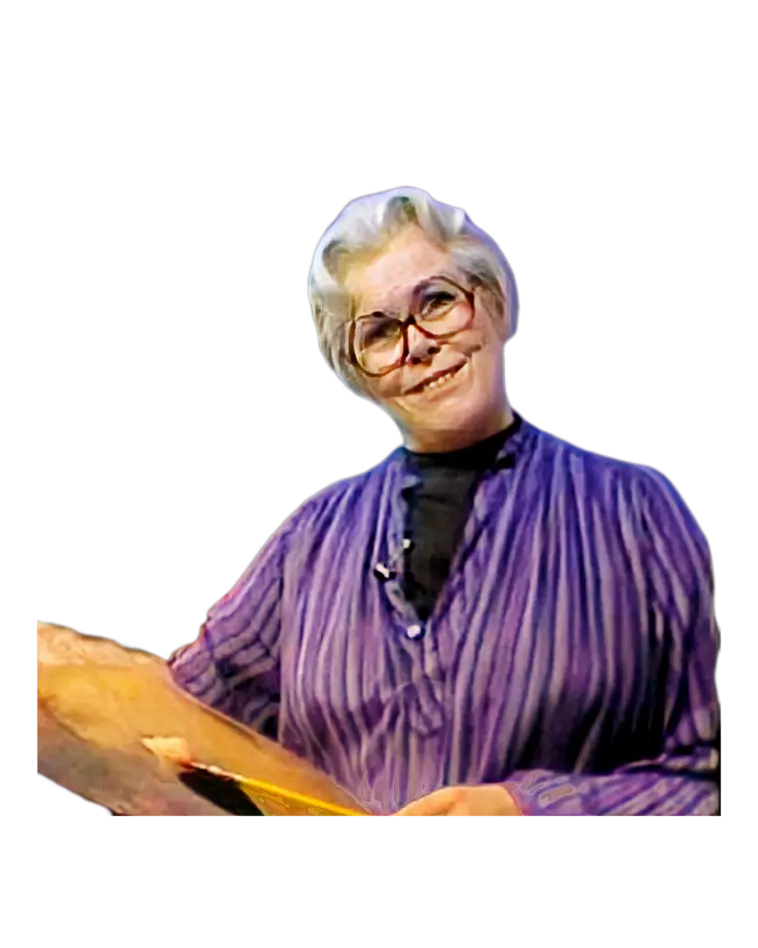

Hello, I'm Helen Van Wyk, and welcome to my studio. Today's session is all about an ellipse—the word for

a circle in perspective, a very important thing to know about—and let me show you what I call the theory

of the ellipse. Uh, an ellipse is a circle in perspective. We see them often in perspective. You'll see

me do this basket of vegetables later, but let me make a circle... kind of. Okay, and let me put that

circle in a box because it's true—you can send a vase to someone in a box, of course, a square box. Now,

diagonalizing a box gives me the middle. This session is not only about the ellipse but about how

important a diagonal is. A diagonal will help you draw things better—many things other than circles. And

so here is the other line. Now, the arc of a circle hits from the center out to here about, oh, 2/3 all

the time; it hits in the center and 2/3 center of each side, and 2/3 of each on, uh, each diagonal. Now,

as soon as we see this flop down in perspective—either lying on a table or tipped as I'm going to do

it—the box becomes a shape like this: this back line gets smaller (this is greatly exaggerated) and this

front line, just as my thumb comes up, comes closer to it. And so we have now a shape like this. These

lines then connect. Well, the diagonal will show you how to find the middle of this new shape, and

you'll notice that this middle is now closer to the back than the front. Again, the center line is here.

Now, to draw this same shape in this new form: it hits here, it hits 2/3 on that diagonal, it hits here,

2/3 on that diagonal, it hits here, comes down 2/3 on that diagonal, and again over to here, over to

here, and now we have an elliptical shape. An ellipse is not an oval; an oval is equal on either side,

so this looks like a... this shape flopped down. Knowing this gives me a chance to understand and see

this basket tipped over with vegetables coming out a little bit easier. So, let me do that painting for

you, or start that painting for you, to show you how it has helped me so much to know about the ellipse.

Why I picked this difficult shape tipped like that, I don't know, but I thought it would be a challenge.

And a challenge is easier met when, uh, we have a little bit of knowledge to back us up. And so, let me

sketch it in. I'm going to sketch it in with black, ivory black, turpentine, and find out where I'm

going to put it. Now, I don't actually draw that diagram that I showed you, because that would be too

mechanical, but that—knowing about that—helps me see this in the way I hope that I get it right. And now

to just flip in some of these vegetables. I just noticed that that green pepper has such a happy

position; it's plopped right up, and this one here... and that's the composition. So important, always,

is beginning with where you're going to place the whole thing. And I think that I'll take a bigger brush

and get rid of the background problem as fast as possible—make it dark so that I can start right in on

the basket. Yes, I've started again—as many of you who already know me—I’ve started on a canvas that's

toned down. I don't start on a white canvas because starting on a white canvas is too difficult, and I

try to make this painting process as easy as possible, because I know how difficult it really is. This

is your challenge, to try to turn this difficult, uh, thing into something that you at least are a

little bit in control of, making it possible. Thought maybe I'd just put a shadow in; well, now, let's

try that basket. The tone I see is lighter than the background, so I'm going to take white and its basic

color—a dullish yellow, raw sienna—and let me try it out. Best way to get the right color is to put the

wrong color down first; maybe I think I'll start just a snit darker... ah, that feels better. Color

mixing—color mixing is, uh, it's easy here, but it has to act; you have to make it act on your canvas.

So this is mostly a matter of putting it down and judging it. Don't be afraid of it; don't think that

you have to have it absolutely right. You don't know until you try it out. Painting is almost like

following your nose; it seems like the picture seems to suggest what you should do next. And that dark

stuff—the dark background color—is seeping into my paint. You worry about it more than I do; I don't

mind that happening at this stage because I'm not looking for an end result. I'm looking for a

foundation of color to begin my picture. Beginnings look like beginnings; ends look like ends. And let's

relegate all these tomatoes as a blob of red... fiddle-dee-dee, I'll make them tomatoes later. Oh, that

one is getting a little bit too much of a push by what I have under it. That's why it's always important

to have a handy little rag to help you with your color. That's better. If it doesn't look right—looks

too dark, or it looks too light—wipe it off and try again. Don't just paint over it; sometimes painting

over it just makes more of a mess. And that is... oh my goodness, I don't like that color either. Wipe

it off, let me try a new place on my palette here. What if I just try, sure, bright green and the darker

pepper—that was a handier way to do it. Start with a light color and darken it. It's much easier than

starting with a dark color and lightening it for these mass tones. Isn't it amazing, in just a few

minutes, you can get into so much trouble! I have all these things to work with now—I have the

background, I have the tomatoes, I have the peppers, now I have the white cloth—all these elements of

the composition to push and try to model and move into an acceptable, pretty pattern. Yes, anyone can

paint; it's true, anyone can paint. If you can see, you can paint, and usually, the thing that makes

people paint is because they desire to do it—not because they think they're going to be great at it. You

don't know that until, oh, hundreds of years later—maybe someone else decides that you were. And so we

stand in front of an easel just trying to make it look the best we can. Don't let the material frighten

you; you can do anything you want with it. Ah, there's the rub—you've got to know what you want, but

sometimes the picture kind of tells you what you want. This picture right now tells me that I should

step back and see what it looks like from a distance because that always gives me a better perspective

of what I've done. It's so important to step back from your work and view it from a distance. I thought

while I step back to get a fresh eye to finish my picture, I'd show you this, um, old chicken in a

bucket. Notice how this is an ellipse. It's a little crazy 'cause it's a crazy bucket, but, um, it was

easier for me to know the exactness of an ellipse so that when I did make this little change, uh, it

still looks sensible and made the chicken look as though it sits in it right. Now, also, you'll notice

on this picture how the tone values—lights and darks—have helped make this elliptical shape round. So

that's really what I have to add to my picture to make this basic mass tone, uh, into something that is

not only elliptical but dimensional. So I'm going to take yellow ochre and white, real light, probably

even brighten it with some cadmium yellow, and lighten it where I know the light is striking it. It's

going to—it’s striking it very hard here. Oh yes, I'm sure you see every little piece of wicker that's

woven. I don't; I'm still seeing the basic form—the basic form that the light is striking here, and then

the light comes along and is striking the thickness as it comes up here in line with the light. Yes, I

could be a little bit capricious about the application. How capricious can you be with a big brush like

that? Maybe I need a little brush and just give a suggestion of the fact that it's woven. Suggest,

especially if you're in the mood to do that—in the mood to just make a quick rendition. Well, you know

that when we meet here, I have to make a quick rendition. I can't paint the way I painted the chicken in

the bucket. That takes long, and I may not be painting the subject matter that you're interested in.

That's why I try to teach a principle that you might use sometime, 'cause who knows what you want to

paint? But the principle of the diagonal and the principle of perspective are very helpful to know. And

I'm going to show you how important the diagonal is in painting landscapes too. So many people are more

interested in landscapes than they are in baskets of vegetables, but since I'm around vegetables every

day—cooking every day in my other studio, my kitchen is my other studio—I paint them. I think it's

awfully important to paint what you know, to paint your own life. Don't paint something that's so

strange to you. But I'm not here to paint; I'm here to teach—to teach you the things that I think are

terribly important, so we make our comment on our own experiences to let someone else know about them.

See, I'm kind of suggesting the intricate of the basket by just a few little suggestions, trying to put

them in. I put them in that way as I am aware of the basic anatomy of the ellipse. And knowing about the

ellipse—that it's a distortion, perspective's distortion of a circle—I know where the center is going to

be, and I always have that center in mind, so it's going to be right behind those tomatoes. Before I

step back and see how the basket looks, I'd like to see how the tomatoes look—or tomatoes, whatever, um,

depends on how well I paint them. If they're funny-looking, I'll call them "tomatoes"; if they're

wonderful, I'll call them "tomatoes." Let me see how their real color looks in relation to the basket

that I've just done. Because a picture is a harmony—a harmony of color reaction, one to another. Oh

yeah, this looks nice with that color, picking out where the light is striking these tomatoes...

tomato—they're still tomatoes. And would you believe, knowledge of an ellipse is helping me place these

bright red spots, because the little stem is a circle, and I'm seeing that stem end in perspective, so

we have fundamental knowledge guiding us all the time. It seeps into our brush strokes, makes our brush

strokes more understandable. Let me put little centers in there, see if that helps a little bit... yeah,

every little bit helps. Strategically placed, of course—that’s what it’s all about, making that brush

hit that canvas with a good aim. And what makes it have a good aim? Some basic knowledge, and the basic

knowledge of the ellipse, the distortion of a circle in perspective, makes your aim better. And here we

have another little ellipse—look at that little ellipse, the end of that pepper. If that were round

instead of elliptical, it would face me instead of looking like it's shooting up in that happy position.

Now that I've related the colors—oh, I forgot that green pepper, the dark green pepper lurking back

here. There's another funny-looking elliptical shape; it has a lot of lumps on it—funny lumps on it. And

so I'm going to make that elliptical shape in lumps like so, and that makes it face this way. Very hard

to be a painter and not ever encounter round shapes in perspective. You not only find them in still

life—let me step back a minute, see what's happened here—you'll find knowing the diagonal will be

helpful in other situations. Before I go back to finishing my painting, I'd like to stress again the

importance of the diagonal. And let's look at this picture and see how the handles look all right in

relation to its entire shape in perspective. How did I get the handles placed that way? Well, with

chalk, let me show you. I'm going to diagonal the box in perspective, and you'll find that the handles

line up now with that. It told me where the center is. For the landscape painter, how many times have I

seen a painting of a landscape, of a house, and the roof looks as though it isn't sitting right? Well,

one way to make that, uh, point correct is to diagonal the box part of the house, and that tells you the

middle, where the peak is going to be. Isn't that fun to know? Very important. So let me go back to this

picture, um, just to put some finishing touches. And since I like to stress things that are important to

know, why don't I focus in on the reflections? Reflections come from the light bouncing back, and maybe

a few reflections into these two tomatoes will stop them from all looking alike. And here, with a

gray-pink coming from the pink of the tomato and the white of the cloth, I have that cloth reflect into

it. It adds a little bit of luminosity. So we have this extra tone value—a reflection. I'm going to

probably have a whole session about reflections; I love them so much. And of course, that old favorite:

the cast shadow and the highlight. I don't know when I'll design a lesson about reflections, but I do

have a lesson already designed about putting highlights on in a situation that's far more important and

needs more care than these. I'm putting these on in the same manner that I did the whole painting. I

don't think you'd like to—I think you'd like to watch me paint a little bit more carefully, which I'm

going to be doing the next time we meet. I think I've—from the start, I've not liked this shape, but

there's nothing I can do about it now. Would I dare? Would I really dare? Oh, why not? Why don't I put

one right here? Yeah, oddly enough, I like that better. You can always paint anything if you mass it in

in a general tone and add a light and the dark. So I've massed it in in a general tone; now I'm going to

add a dark to sit it down. I'm going to add a shadow to give it dimension, and I'm going to take a nice

light tone and pop some light on it right here. I know it's funny painted, but it helped the composition

I think. Composition is always important to me. It's an important ingredient. We work with ingredients,

and painting—all the ingredients add up to the flavor of the picture, just like cooking. And so I'll

talk about an important ingredient next time: the highlight. Or maybe I'll use my other studio and teach

you how to make soup.