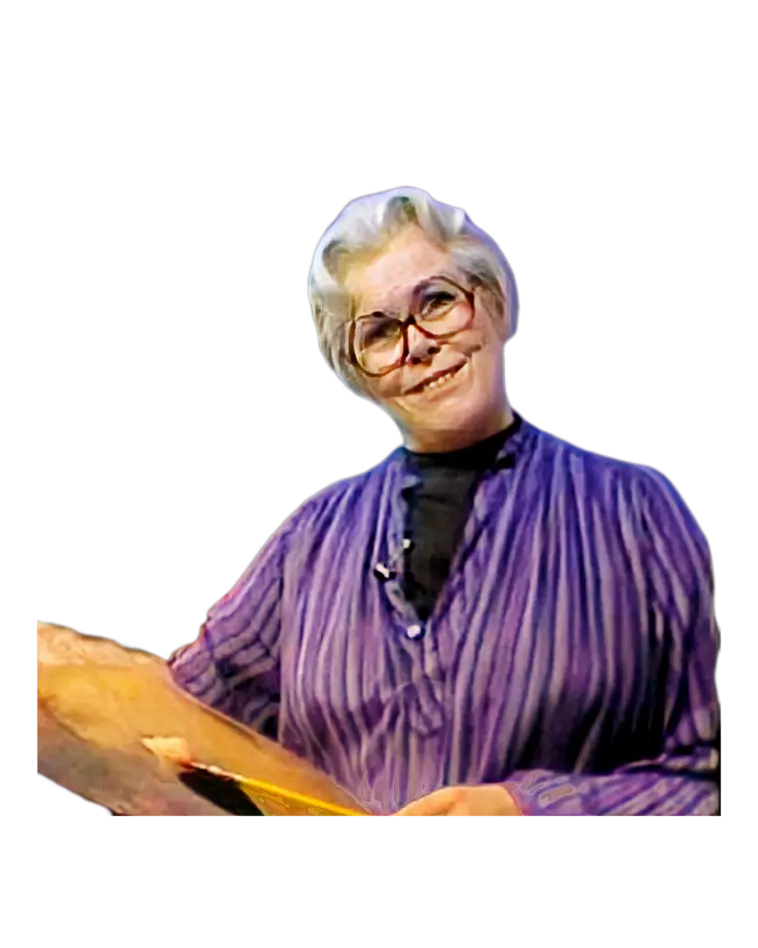

Hello, I'm Helen Van Wyk, and welcome to my studio. This is the picture you'll see me paint from the

first stroke to the finishing touches. I've aimed most of my instruction at procedures and painting

techniques, knowing full well that the painting process is too complicated to cover in just one painting

session. Before I dive into discussing still life, let me acquaint you with the painting components that

apply to any picture, whether it's a still life, a portrait, or a landscape. Every picture has a

composition, which is the arrangement of the subject on the canvas. Composition is further defined with

drawing, which includes structure, proportion, and the perspective from which you view at the

composition. Tone, light, and dark give dimension to the subject, and color certainly adds luminosity.

The paint itself, and its rhythm of application suggested by the object's forms, gives a quality or a

personality to the picture. Every picture has edges—found, sharp, such as this, and lost, such as this.

These found and lost edges help present the dimensional quality on this flat surface in that sharp edges

project and fuzzy edges recede. Before we go to my easel, I would like you to get a glimpse of the

subject matter that I'm referring to. This is the still life arrangement. I arranged my lighting to come

from the left. The lighting is important since paint is a physical substitute for the effect of light. I

will be putting my paint onto the canvas the way the light is shining on this subject. The subject is

made up of reflective and non-reflective objects, such as the bottle—highly reflective—and the grapes,

not so reflective. I will be painting reflective objects pretty much by focusing my attention on

highlights and reflections, but on non-reflective objects, such as the crock or the apple, I will be

doing them primarily in body tones and body shadows. Now, finally, let's go to my easel. I am going to

do a tonal underpainting with acrylic. I have black and white, and I'm going to be mixing tones of gray

to lay in a whole foundation for my subsequent applications of oil. But why don't I start right out and

show you how I always approach a composition, and that is by organizing the size of the entire subject

on the size canvas that I have. Actually, I only know four things about this canvas: this side, this

side, this side, and this side. And so I want to make this fit on that, so that's where I start. I don't

start in—I start from the out and work in. So, I'm going to say I don't want that apple to be any closer

to the edge of the canvas than there, and the tip—the right is that little tip of the lemon—and I don't

want that any closer to the edge of the canvas than there. Of course, this is how I want it, how I think

it's going to look nice. One of the things that I think is important to have things look nice is not to

have this distance and this distance equal. Then I don't want anything to go out of the canvas at the

bottom, so I'm going to make a whole mark down here. I think the tallest thing is going to be the

bottle, and that's going to be up about here. Those are easy decisions to make, much easier than trying

to draw each one. Really, it's so much better to find out where you're going to draw, and that is really

the function of the placement stage of composition. Now, let's zero in on this overall arrangement, and

not even draw—just still see if we can organize. So, maybe this blob of shape could indicate the apple

and the lemons, and then a shape here—well, not a shape, but a size—to indicate the little copper thing

and the apple. Then I have the jug pretty much here, and I can feel that the grapes are going to be

here, and the apple is going to be here, touching that, which I had decided before. The bottle is going

to be tall, right about here. These are just indications as to where I'm going to aim my paint to

indicate the drawing. Many people are afraid to do this because they're afraid they're going to wreck

the canvas, but you have nothing to lose at this point. Why don't I make a few more marks just to give

me a feeling of security? It's important to know what you're doing at the time and feel that you can do

it. So, why don't I say this is going to be the bottom of the apple. Where is the bottom of the bottle

in relation to it? Where do the grapes come in relation to that? Where is the bottom of the stone crock

in relation to these things? Painting or drawing is not looking where you're going—it's looking where

you've been. These things can help with the final effect. Many people feel as though they have to be

fantastic at drawing, but you can learn to draw or learn to draw better if you realize there are three

factors to drawing: proportion, perspective, and anatomy. Now, proportion is really the first thing

because it is the most important. If you get the size relationship of one thing to another, you can then

have an overall plausible look. Surely, the size of this lemon that I'm sketching in now has to be the

right size in relation to the apple. This is just a little bit more development of the composition down

through here. I think maybe you also noticed, or I'd like to point out, that I have everything either

not touching or completely overlapping. It's never a good idea to have things just touch, because if I

had this apple here—and I have a shape that's going to be the side of the copper pot—if I had that apple

right here touching it, it would look as though it wasn't in back of it. So, to make it look as though

it's in the back and to give that beautiful depth dimension, we just make sure to either move them apart

or overlap them. Now, the height of the bottle and the anatomy—now I'm in the drawing stage. The

composition is pretty much settled, and now I'm getting the structure of them. Anatomy is recognizing

the anatomy of a subject, which is the key to getting it to look sensible. An apple is a little round

shape, and it has a little hole here, which is kind of an inverted cone. You see, it's really this, with

a stem sticking out, but it's infinitesimal. So, knowing basic shapes is very important. Now, the

proportion of the bottle—and of course, the bottle's anatomy—is that it's a straight line, and then you

just have to draw equally on either side, taking into consideration the elements of its shape. It has a

top section, a neck section—I call this the shoulder section—and then the easy part. Now, we have the

bottle, and the stone crock in relation to it—it's again behind it, and it's going to be about here. The

bigger part of the shape comes first, and then I find the smaller part of the shape. Of course, the

handle is of no consequence now because that can always be added later. Now, I'm going to have a chance,

I hope, to decide exactly where this apple is going to go. Yes, right about here, maybe here. I'm going

to make this a little smaller, and the height of it in relation to what I've already done is here. This

is going to be the little copper pitcher. Then I reiterate with a few lines to give me a sense of

security for when I'm actually going to paint this. This is where its little blossom end is—or no, stem

end. Now, the anatomy of the lemon—yes, I see it flopped down, so the top plane gets quite a bit smaller

because of perspective. Now, perspective distorts the proportions of things, so proportion can help you

with perspective because if you know the size relationships of one thing to another, you almost

automatically get the perspective. It's a fringe benefit. Now, I do think I have to do something about

this and make it an interesting shape of grapes. They're going to come in front of the bottle, then it's

going to have this frontal part, then a part that jumps up here, and then a stem. And charmingly, I do

see them through the bottle, which I'd like to take into consideration—not that I'm actually painting it

now, but I'm putting it in my memory bank for later on. Realize that the beginning of a picture looks

like a beginning; it doesn't look like the end. I do want to show that the person didn't drink all the

wine. Now I want to establish the vertical plane and the horizontal plane. Many people start with that,

but I always do it in relation to my arrangement. This is the one place I would not have it—right here,

right on top of that apple, because it would look as though the apple is holding up the table. It has to

intersect at a planar place. Many people are afraid to make these big, bold lines, but painting is a

matter of seeing something. You can't correct it until you've done it. They say that a painting is a

record of a series of corrections, so you visually and artistically respond to this, and then see how it

looks. So, make it bold right from the start. There's no reason to fear the black canvas in the

beginning. You will fear it if you think of it as the beginning that has to be the end. Now, the

progression of application, just the values of the subject—it seems the practical way is to do the

background, the jug, the bottle, and so on, until I come to the foreground. I've mixed black and white

acrylic to fill in the darker background. Again, this beginning is done not for any other purpose than

to serve the next stage of the picture's development. You will see, in the progress of this picture, how

beneficial this tonal evaluation of the colors will be. I don't want to get ahead of myself. I would

rather talk about what I'm doing as I do it. I would like to say that I do have a policy about doing

large areas, and that is: my stroke rarely gets much longer than an inch and a half. Big, bold things

like this don't really look as atmospheric and represent air as much as little strokes, no longer than

an inch and a half. The value of the jug, in relation to the tone that I've just used, is lighter, and

I'm already doing something that's a basic technique of mine: the first thing I paint, I paint bigger

than it is, so the next thing I do can cut into it. Now, I'm filling this side of the jug with a darker

tone because this is where I see the body shadow. I'm also going to make this darker because this is

going to be the cast shadow from it, to help it look as though it takes up some space on the canvas. I'd

like to get the background darker here, and darker here. Why? Because I think it's going to look better.

A change of value in the background can really only ever touch the subject or touch the edges. If, for

instance, I do this, that distracts from the overall composition, because that's a change of tone that

is not touching the subject or touching the edge of the canvas. I'm going to mush that lighter tone in

over here, though. Why? Well, that is really where the background gets lighter because that's where the

light is going. The light's coming from the left, hitting these, and on its path making this the

lightest part of the background. I really don't just paint that dumb drape that's behind my subject—I'm

really painting the air that is wrapped around the arrangement. The bottle is made up pretty much of

just reflections, not really having any tone of its own, so I think it'd be better just to take it out.

Oops, no, no, no—too light for over there. I'm going to destroy that edge because, as I said, I think

that would be more of a problem for subsequent stages of the picture's development than right now. If

you think of the simple steps, just like walking a thousand miles, you've got to do it one step at a

time. You can't make it one great, big, giant step. But it's sometimes kind of hard to find a beginning.

A beginning in painting is always the arrangement of the values that are contrasting each other to make

the shapes. Yes, it looks as though these grapes are a very light color, and we think of them as light,

but in this situation, they are darker than the crock. Very often, preconceived ideas of what we think

the object is like rob us of the chance to record it as we see it at that particular time. Yes, the

liquid in here shows up darker, the apple shows up dark on that side, plus its cast shadow. There's a

shadow here where this bunch of grapes recedes back, and there's a cast shadow from the grapes over

here. This apple reflects light because it's in the dark situation of the cast shadow from the jug. I

work, I do my underpainting in acrylic because it's fast-drying. It also covers much more substantially

than oil. The Old Masters used tempera for their underpaintings. Acrylic, in the 20th century, is the

substitute or the replacement for tempera. So many people who have seen me demonstrate are shocked at

the fact that I start this way. So many people think that color is what builds a picture. But of those

six components I talked about before, color is the one that is inconsequential. It decorates; it does

make the picture look luminous, but it does not really show the drawing, and it doesn't show the

dimension. The tones do, and the contrast of values also determines a picture's composition—the

all-important composition. And again, I have cast shadows here from these. I try to initiate this very

broadly, without any detail. After all, detail is the development of a larger mass. So, I put the larger

masses in first, and then refine them. But I would say that everyone is kind of stuck with his or her

own "paint writing," like we're stuck with our own handwriting. Some people are very neat; some people

may have a tendency to make a looser interpretation. It's a matter of thinking about what's important at

that particular time, and to me, this picture's overall composition and its placement on the canvas are

more important than anything else. I can develop everything else in the next stages, because I have to

see how it looks. Then, if I see how it looks and I think it looks all right, I can go back and fix it

up a little—maybe lighten this. I want to have a chance to make a beautiful outline of the bottle, so

maybe I’ll take that away. In the beginning, I like to keep all these shapes very vague; after all, it’s

just a foundation. I always call an underpainting "under" like a foundation garment—it makes you look

better in the end. And surely a smaller brush would be the handier implement to zero in on this object’s

shape. This has to have a little indication of its stem end. This is such a complication over here where

this lemon is sliced, that for me to have a lot of activity in my underpainting now would almost be a

hindrance rather than a help. So, I think I’m going to decide to take it out and put more of the copper

pot in, and make believe it’s not there. Painting is just a matter of figuring out a way to make it

easy. So, you can see that now that I know the size the whole bunch is going to be, I can then divide

the bunch into grapes, because before, I couldn’t think of the bunch and the grapes at the same time.

This is also a beautiful section that I want to do as well as possible, where the grapes are going to

encounter the jug, so I’m going to not have that shape in at all, so that I can move that up against the

jug. Now, this tonal evaluation of the arrangement and the subjects of the arrangement could also be

done in oil, in thin washes of, let’s say, burnt umber for where you see it dark, and leave the light

canvas wherever you see it light. I like this approach because it substantiates my color. Two coats are

always better than one, especially when you’re working in oil, because oil paint is not as "masculine" a

medium as many people think. So, this represents step one. What I’ve done is to review: first, I made

these marks, which I call the envelope, that situates the subject on the canvas. Then I started to make

a lot of lines to help me get the feeling of the objects' proportions in relation to each other and

their anatomy. Then I started to record the lights and darks caused by the light coming from the left

and shining over to the right. We’ll be ready to do the next stage as soon as this acrylic underpainting

dries. Now, I start out with the background, and I’m going to make the background brown—a

greenish-brown, which is a version of yellow. So, I’ve taken burnt umber and a little sap green, and I’m

going to see how this looks. Yes, I think that’s kind of a rich color, although you have to put it down

to see if it’s going to work. And I did put this down and saw it in relation to the color of the copper,

and maybe it’s not going to contrast enough, so I think I’ll make it a little greener. Yeah, that’s

better. Thin the paint a little bit more so that it flows on better. Now, I would like to tell you that

it’s a great joy to put this dark color on a toned canvas because this color on a white canvas wouldn’t

look as rich. And maybe you see some streaks as I work—I see them too, but I’m not going to worry about

them. I want a smooth background, but I can’t lay in the color. Why don’t I go right into that bottle

with the color of the background? See, since I see that through the bottle, I can’t lay in the color

that I want and get the appearance of the color I want in one application. Painting in oil—in an

important way, being able to handle oil paint well—is to recognize its limitations. Don’t expect it to

do a wonderful thing all at once; you have to work into it. If ever you get a glare as you paint, tilt

your canvas forward. Don’t spin the easel around and around; just tilting it toward you will be the

solution to that problem. Now, I want to give it an effect, and so I have a brush that is softer. Did

you believe this is a hake brush? All my brushes are also listed in that pamphlet. This is a hake brush,

but I call it my “Poopsy dooo” brush. People say, “What are you doing now?” I say, “Oh, I’m just Poopsy

doing along, trying to make that background talk to me and say, ‘I look decent.’” And this slopping in

the background is not that fancy, but the slopping in of the background color on the edges of that jug

and on the edges of the copper pitcher will help me execute those found and lost lines. I am now going

to start the development of the jug. Its color is yellow, its tone is light, and the yellow is a

low-intensity yellow. So, I’m going to use this low-intensity yellow and lighten it with white. Why

don’t I clean off a mixing place? I’ll take the white first, put the yellow into it, and see how it

looks. Actually, I feel as though it’s too bright, so I’m going to dull it with a duller yellow—burnt

umber. And I’ve come up with this, which seems like a good basic color. I’m going to take another brush

and mix the shadow color because this is a non-reflective object. I usually paint non-reflective objects

with two tones: the body tone, where the light strikes, and the body shadow, where the light cannot

strike. I am mixing a violet—the complementary color to yellow—and I’m going to try that out here. I

think I’d like it darker—that’s better. And so, this pole I have in my hand is called a maulstick. It’s

going to steady my hand as I go—steady as we go. I have a filbert bristle brush, which is a brush that’s

set flat at the ferrule but comes to an edge. And so, that’s where the body tone is. Now I’m going to

cut the body shadow into that. There’s a feeling that... I think I’ll make it look as though the cork

isn’t there—the cork that’s in it is not a nice-looking cork. Well, that little top sets within the

fatness of this, so I make this come down further, and then make that go in back of it right there,

leaving a lost line. This cylindrical top is casting a shadow on the top, and a little bit of light is

falling around it. I think I mentioned earlier in my painting demonstration that the first thing I do is

paint in bigger than it really is, so the next thing can overlap it. So, why don’t I put this whole body

tone in, going over the edge of the bottle, because that’s going to go in later? And I’m going to put

that in deeper also than I actually see the shadow. Now, I don’t like the brush I chose for the shadow

color. I’d rather use this one—one with a flat end. The other one is a filbert. So, this is the shadow

color, thicker, more of it. So, let’s mix more of it. And let me now put in the shape of the shadow on

this non-reflective object. As soon as you find that your brush doesn’t slip along the canvas easily,

use a little bit more medium. And now, here is the all-important turning edge, which is fundamental when

painting non-reflective objects. This part right here—this is the part that seems to be so difficult for

beginners. It’s where you want these two to blend together. Well, here’s my way of doing it. I take a

darker version of the body tone—less white in my mixture. I have this, and I make teeth. I’m trying to

blend those two together, so I blend them together with a continuous wiggle stroke, and now fuse them. A

big blender, or just a large brush, is very helpful at this point. I would like to now extend the

progression of this, or the appearance of this jug, a little bit further by putting the color back into

the shadow. See, I have yellow, I’ve turned it into shadow with violet. Now, with a darker

yellowish-orange, I’m going to put color back into the shadow to stop the shadow from looking like a

vacant area of illumination. There’s always enough reflected light in the room to put color back into a

shadow. And because I want the interpretation of this subject to be a little bit mysterious, I’m going

to take my background color on this bigger brush and obliterate that line. Actually, I think this is the

beautiful part—the more mysterious you make your shadow areas, the more beautiful the illuminated areas

will be. Big areas, big brushes; small areas, small brushes. A small brush would never be able to give

you the solidity that this application with this larger brush does. If you just slide down between the

body tone and the body shadow with a more intense color, you can affect a blend. I think it’s kind of

important right now to suggest the beginning of the structure of these handles. Well, it’s here, where

there’s a raised part of the crockery, and there’s a raised part of the crockery over here. And I would

like to line one up with the other—it shows here. You can see where all the little details are better

added to the basic structure than included from the start because it gives you a chance just to make

your paint neat. I always say, if it can’t be arty, at least be neat. Make the paint look decent. And

this is a cast shadow from that handle. You can see that when I do any of the painting that brings out

the form very distinctly, I’m using a sable brush. I feel as though this is about as much as I’m going

to do to the jug. And the natural progression seems to be that I should do the bottle. Now, I’m going to

start painting the bottle, and I’m going to look for all the colors that I think are part of the back

part of the glass. So, I see the crock, which I’ll make a start with—the crock color. Then I’ll add

green to record this part. Actually, I think that I should use more green—it looks too light. That's

better. And so, looking through the front part of the glass, I'm recording the color that is the back

part of the glass. Yes, that shape becomes fused, and it slides up here, and I see a slight light

reflection there. The green looked too light, so I added black. Ah, that's better, to suggest the other

side of the bottle that seems to be lighter right here on this corner. Let me get in front of it a

minute—that's it. The thing that intrigues me about the bottle is all the things that are seen through

it in a distorted way: the stone crock, and then I see the white tablecloth reflected in it too, or back

there, and it's enlarged. The table line is here, but this is kind of enlarged here slightly and

delightfully so. I see the grapes through the bottle. When you have a setup of still life subject

matter, look for the things that you think are lovely-looking and make an issue of those. If something

doesn’t look lovely, just forget it, make believe it isn’t there. But I do want to show the lid, and I

think in terms of slices or planes, but why don’t I talk about that when I do the copper? I see the top

plane of the liquid, and this is a grayish red. I have to cut into that grape that’s going to be in

front of it later. Don’t ever be afraid to overlap. It makes the paint look so much better. If you don’t

paint in an overlapping fashion, it looks as though the picture is a colored drawing rather than a

painting. Now, the bottle so far looks naked—it doesn’t look as though it has its clothing on the front.

Well, that’ll come later. I do have to take a smaller brush and work out the complication of the top,

and I surely would never let these come on the same plane. I’d have to have it tall. Well, there’s a

little ceramic stopper. That ceramic stopper has a shadow. Remember, the light is coming from the left,

so any non-reflective object, such as this ceramic stopper, is going to have a light side—that’s the

left side—and a dark side, which is the right side—that’s the shadow side. Would you believe that this

little rubber has light and dark? All non-reflective objects have a light side and a dark side—not true

with reflective ones. They really are a mass tone with capricious reflections depending on the

environment they’re in. Very often, light appears over here on the shadow side because the light can

pass through its transparency. I think you’ll notice that I have a brush with a beautiful chisel-like

end, and because I didn’t have the outline there, I can make the outline with brush strokes, giving that

painty look. This has a little bit of a dark interrupting it, and now I can introduce a little bit more

feeling of green, taking away the background color. And so, that’s as much as I feel I need to do on the

bottle at this stage. It is at the same stage of development as this, and I have to now go on to the

rest of them and carry the development of the picture just to that stage so that the picture matures

completely all at once. My next problem, or my next enjoyment, is to develop the grapes and the apple

that are in conjunction with the bottle. I think I’ll do the grapes first. And so, on my palette—as I

said, my palette’s my thinking place—if I’m going to have to do these grapes, I have to think about

what’s behind them. And as I look at these grapes, I see what’s behind them—a lighter tone of the crock.

I always police the area first, meaning I see how the surrounding area looks in relation to what I’m

going to do. So, I’m going to now actually lighten here before I start the grapes and clean my brush in

that big can of turpentine. And now, grape color: green and yellow. A little yellow-green and yellow

ochre, and I’ll be able to now cut dramatically the shape of these grapes against that color. Painting

is never filling in lines; it's making lines per stroke. I think constantly making decisions. If you

like to make decisions and wrap one after another, paint. Shall I make that come in front of that now?

Yes, why not? Should I make another one come in front of it now? Why not? If I wanted to develop this

section better, I would save those two grapes for later. But I'm not going to get involved with those

grapes in the middle because I have on my mind right now the grapes' silhouette. When the paint doesn't

seem to cover easily, thin it with a little medium. There are big shadow areas on the grapes. I'm now

adding the complementary color red into the green, a reddish violet—not to shade every grape but to help

shadow-wise the bunch because I have a cluster coming forward. One of the difficult things about

painting is that you always are looking at a finished product. You're seeing reality and you think that

you should get that reality right away, but you're not painting reality; you're painting an

interpretation of reality. So even though I see a lot of things going on here, I know that I just want

this cluster to come out, that to go back. Light makes it come forward; dark makes it go back. It seems

practical, and that's what I said my painting technique is: just reasonable and practical. Rather than

try to do this whole shape of these grapes as they meet the table, I should have the table in first

because they're overlapping the table. So again, I'll save that for the next stage. Now, the apple in

front of the bottle is also seen against the light table color, and I think I should put that in. Again,

always look at the surrounding area and adjust it before you actually do it. Now this mixture is where I

employed gray. I took black and white first and mixed my yellow into it, and I'm going to overlap with

that the outer periphery of the apple. See a nice little shadow behind the apple? Here, put that in too.

This line from background to foreground in still life is an unnecessary evil. I hate to see it as a

straight line because we deal so much with arc shapes that a straight line becomes so peculiar or almost

more important. So I like to fake it and make it very nebulous because I know people always ask me,

"Helen, how long did it take you to do that picture?" I say, "A lifetime." It's the time you spend at

it, at actually doing it, that is fortified by the years of practice that you've had. It also is

dependent on the mood you're in. So people say, "How long did it take you to do this picture?" About an

hour and a half and 50 years. Oh, right from here I can see what I have to do. Hello, I'm Helen and

welcome to my studio. I have to go back and add that important tone value. Yes, you guessed it: the cast

shadow. Maybe I was Rembrandt's wife. I paint what I know, but I need my eye to judge how it looks. If I

were in my own studio instead of a TV studio, I'd have my music on, I'd have the coffee pot on low.

Hello, I'm Helen and welcome to my studio. So when I step back, I'd have a slug of coffee. Magenta

violet is a crazy little color; it does wonders for yellow. Just tones it down. Painting is a matter of

adjusting—adjusting to what's happening, making it work. It's the creative spirit of . As dear old Rosco

said, "You make it, you break it, and you make it again." Hello, I'm Helen and welcome to my studio. I

always start adding and trying to develop the surrounding areas, which is called the negative space,

starting from the focal area. I would never start on the corners of the canvas because as I reach out

toward the edges of the canvas, I like to have the interest dissipate. Now I can put the white or

off-white. Yes, I work from the top down because I can watch the expensive end of the brush—the part

that you're watching. See what I'm doing? What's going on underneath? You can't see, neither can .

Hello, I'm Helen and welcome to my studio. What I want to teach is more a matter of procedure rather

than painting, rather than drawing. Again, practically artistic or artistically practical, painting

outdoors is very challenging. It's amazing that your pictures will be acceptable if it's consistent. The

way you paint your picture will be acceptable if you have a focal area. Hello, I'm Helen and welcome to

my studio. It's true that painting—the act of painting—is a test of taste. It tests your taste as to how

it looks, not how it is, but how it looks. And now for the apple. When I mix the color, I'm going to mix

the red that I see right up here. I'm going to take this cadmium red light and Grumbacher red. I'm going

to try it out. Nice! I've got to lighten it, though, and make it yellower. Yes, now I wipe the brush

off, load it so that I can have the end of the brush record the shape back here. Every observation seems

to demand a slight variation of the basic color to give it interest. Another reason why a palette is so

important is because your colors are so close by. I'm now developing the colors of the body tone. The

color is getting a little darker here just before it falls into shadow. So now darken the red—Alizarin

crimson and Grumbacher red mixed together with its complementary green to reduce its intensity. Look

what happened here—paint in the shadow. If you want to fuse those colors, don't add too much pressure on

the brush. Of course, the brush has to be loaded. This is why there's a constant reference of your brush

back to the palette. Just as I wanted the shadow side of the jug to go back, I'm going to do the same

thing here. I'm going to obliterate all this and make this a plain shadowed spot, combining the body

shadow with the cast shadow. The underpainting has enabled me not to have to paint too terribly thick,

which gives me a chance to add a strange color on a strange color, meaning this bright green right on

that red, and have it show because actually that red is not that thick. My hand is not educated to draw

this; my mind is educated to draw this with paint because I know the anatomy of an apple. Going back to

what I said before, this is a little inverted cone, so it gets light here and dark there. I know that

the apple is made of five sections, so I do this and this. I say if you want to do a good painting of an

apple, buy two and eat one. See what the core looks like. So now I'm going to continue on to the other

side of the composition. So again, since I have another apple to paint, I'm not going to clean my

palette, but I am going to take another broader view of the whole picture as it's progressing. This

demonstration is about basic painting procedures and techniques, and this is my most reliable painting

procedure and technique. You'll notice I have a little copper pot, very similar to the one that's in the

composition. When I want to record anything, I try to analyze its entire shape in segments. I call them

slices. Could you imagine this little copper pot as a loaf of bread sliced standing on end? You're aware

of each slice. Well, now let's examine each slice of this copper pot. It has a top slice that's plain,

then it has a thickness, then it's on a little pedestal, then it's on a bigger pedestal, then it has

this sloping section, then it has this line, another sloping section, then it has the fact that it is

detached here. This is where it has its little spout. Here, it doesn't just slope in; it comes down a

little, then in and out. Its fattest part comes in, down, and then a base. So we can almost say that it

has 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 slices. If you look at something very carefully, you

then know it, and your brush will be able to record it. I have been actually doing this as I have been

painting these things. I started here at the apple, then came to the part that had the little

indentation and then did the front part. That's how I'm going to proceed to do this little copper pot.

But before I do, I have to do the apple behind it. That apple has a very lost, vague line because it is

partially in shadow. With my ball stick to steady my hand, I'm going to ease it in gradually. I must get

this apple painted in before I can proceed on the lovely little copper pitcher. Another basic, reliable

procedure would be to always put the more fragile colors in first. This apple is yellow and red, and I'm

going to put the yellow part in first, again bigger than it is, so that I can ease the more dominant

color into it. You'll notice that there's always an action to the brush, and from the action of the

brush, the paint results in a certain appearance. That's called the rhythm of application. Really, any

stroke will not do; the stroke has to be inspired by your observation. Not only your observation, but

your analyzation of what you see. So we don't just look and paint; we analyze and paint. It's very

important to have your rag close by to wipe the brush down when you feel as though it is too heavily

saturated to affect a blend. I'm going to pull that apple in further than I think I need it to be able

to now do the little copper pot. Starting from the top down, I'm going to do it a slice at a time with

two nice brushes. I'm going to mix up a general tone, and because metals have a magnificent highlight,

I'm going to sculpt that object shape by its basic tone and its highlight. The tone that I see at the

very top is the basic tone. The next slice is being affected by the highlight. This next slice is

primarily the basic tone, and the highlight is here. Where do the highlights hit? Wherever the plane is

directly in line with the light. This happens on any concave or convex plane, in line with the light,

not in line with your point of view. Appreciating the object's shape in slices will make you able to

draw better. I keep stressing that because people are always worried about drawing. This makes it

sensible, and sensible seems to mean, in painting, right. You don't want it to look realistic; you want

it to look plausible and recognizable in terms of paint. After all, I don't have a little copper pot on

my brush; all I have are the tones and colors that I see on the copper pot. This slice comes down. An

educated finger is always a handy thing to have, and now we have this dramatic highlight that hits on

the concave plane and on the convex plane, in line with the light. This is happening on this sloped

form. Be afraid to have these colors mush together. Years ago, when I studied as a child, my first art

teacher said painting is organizing successful accidents in rapid succession. Now I'm going to cut that

shape off with the next plane down, and here I have another little highlight because it bumps out.

Again, put it in bigger than it is, so I can ease it in, and now we're down to this plane, the down

plane, and thus the object seems to grow under your brush strokes. I can't really stop now; I see

another slice, and that is its rolled base. Now the copper pot is done, only in highlight and body tone.

There are areas that are so much away from the source of light that they are actually in shadow. Of

course, they're all going to be on the left—I mean, I'm sorry, on the right—opposite from the source of

light. Constantly be aware that you're painting what the light does to the object, not what the object

really is. That's a capricious dark odd that it's there. Shouldn't be on the light side, although

reflective objects often get very dark things on the side toward the light. If you see something about

the subject that you think is intriguing, put it in. Don't be too mechanical. There are reflections on

that copper pot too; that will be a great benefit. But I like to save reflections for later. Why don't I

continue right along now and do the red apple? When you see a color that looks as though it doesn't have

white in it, then you can go reach the color first. As soon as you think that it's, you can always feel

that it has white. So, I'm going to take this red and put it down on a thing on my palette, judge it,

'cause I can look at it. And look at this! I think I could even put a little alizarin in this to get

this a richer red to start that. Yeah, I like it; use it. That's where the light strikes. Yes, the light

can strike in the anatomy of its stem end. I'm going to put that in, and now I'm going to first, with a

darker red, begin the shadow. And then with the complement in that darker red, paint the shadow. This

procedure and use of color is an analysis of the principles of nature. I didn't invent them; I just am

aware of the nature of nature and use nature's characteristics in my painting to get that natural look.

And you could see now that there would be a real necessity to just stop a minute because I'm going to be

drastically putting yellow against brilliant red. Look at the complication of shape I have to encounter

and deal with. The slices against the apple and then the half a lemon is also against the apple, and the

slices behind the lemon. This very often seems as though it can never be recorded in paint, and yet

these reliable painting principles and reliable painting techniques will be able to manage that

complication. And now over to the canvas, we're going to wipe away some of that red first. And now with

a loaded brush, the paint right on the end of the brush, I'm going to put the shape of the light of the

membrane right against the apple. I really don't care how thick it's going into shadow here, how thick

this shape becomes, meaning thick from top down. Because I can shape it in with the next tone down,

cutting it down to size. That stroke could go down very far; I'm not interested in that. I'm interested

in this. We then have the meat of the lemon in shadow. Remember all these mixtures are in that pamphlet.

Cutting that further down purposely, further down so that I can make a nice swipe with the brush to cut

it off. It makes a neat application, and then that can be cut off with the rest of the—oops, that's the

wrong color. Greener. It'll color back into the shadow, and now I'm ready to cut the half a lemon

against what is already there. You can see how important it is to overlap. So now I have the meat here

again, ignoring how thick that is being painted because I'm going to cut it down with the next tone and

shape. I see the light membrane coming right at me. Make this down further than I want it so that I can

make an immaculate-shaped lighter membrane in front of it. The brush was never really meant to make

skinny little lines. You have to figure out a way to make skinny little lines, especially light ones.

Now this is the light side, darker just before it turns into shadow, and now the shadow is going to cut

that in front of that slice. Then the bottom of both of those shapes are going to be cut down to sides

with the all-important cast shadow. Now doesn't that seem like a practical, logical, and easy way to

deal with that part of this picture? Racing right along, let's see how putting in the all-over table

tone will affect the appearance. See how colorful all this is? And this gray is so colorless, which

proves that you can never paint anything with just black and white. It has to have color imparted into

it. And so this white tablecloth has color in it—yellowish in this case. I know opportunity to fix

shapes. I want to do a better job of that cast shadow, so I'm going to cut into it with paint so I can

shape into it. And here again, remember I said that these grape shapes should come over the tablecloth

and all this back in here. Since now this is in the yellow, uh, off-white family, the shadow is

violet—the complementary color to yellow. Light is made of three colors: yellow, red, and blue. You have

to use yellow, red, and blue to record the effect of light. So when you're painting something yellow,

you have to use violet, the combination of red and blue. Why? Because that's the very nature of nature.

You want your pictures to look natural; you will have to abide by nature's laws. I do this because I

want to follow through. And this ends the—well, no, let me fix, let me fix the shape of this shadow

here. And let me fix the shape of these shadows here. And again on the bunch of grapes, this shadow

here, and have the shadow conform to what's causing it. I have a beautiful lighting effect in that the

light is passing in back of those grapes right there. Wish I could get the color I want. Maybe that's

better since this program, or this demonstration, is primarily on basic painting techniques. I haven't

talked about composition; that will come at another time. But I'm suggested to—or my, what I'm doing now

suggests me mentioning it—that the all-important factor of composition is a focal point, which can be

very much established by having a tremendous amount of contrast in one place. So we—oops! There's lots

of oopses in painting. I say "oops" a lot. And now we're at the end of, let's say, the second stage. I

had the planning stage, the underpainting, and now I have developed all the objects to a point that I

can further develop them with the strong accents of light. I thought I'd take this time out to introduce

you to my palette. The leaflet has all the color names listed, so I can talk only about the palette's

function—a very important one. Many people think that a palette is just a mixing place. I think of it as

a thinking place. Paintings are made of shape, tone, and color. The tones and colors are what I decide

on my palette, and then let my brush worry about the shape. I am left-handed; I guess you've noticed.

And so I set up my palette backwards. I read from right to left, in that I put my white, a lightening

agent, at this end and go all the way over to here to black, a darkening agent. Although I don't use it

for that purpose, I use it primarily mixing it with white to make tones of gray. I then add a warm color

into these grays to make the gray warm, or a cool color into the gray to make it cool. There are only

six colors: yellow, orange, and red, violet, blue, and green. But they vary in three ways: tone, light

or dark; intensity, bright or dull; and hue, which is the particular quality of each color—yellow being

maybe greenish, or yellow being kind of orangey. And so I have on my palette the three warm colors:

yellow, orange, and red in bright versions, in dull versions, and even darker dull versions. The cool

colors are here grouped together: violet, blue, and green in rather dark forms but quite bright. So I

find that I can conclude a successful mixture by asking four questions. For instance, this—I ask myself,

"What color is it?" It's yellow. "What tone is it?" It's rather light. "What intensity is it?" It's not

too bright. "What is its particular yellowness?" It is maybe more orange than green. And so I take white

for its lightness, a medium yellow for its color and intensity, and darken it or orange it with a little

bit of burnt umber. And so I quickly ask these four questions before I start mixing a color, and then

see how they compare. So now it's time to go back to my easel and continue this picture in oil in color.

What I'm going to do to each one of these objects—starting out with the jug, seems to be what the

beginner painter wants to start with. And here I've saved all this for last because it is the very

extraordinary lovely things about each thing. Starting with the jug, I see a highlight, that

all-important tone value, and it hits here. Here's a little convex plane, here's a concave plane, and

here's a great big convex plane. I see one here and here too. I can't leave them like that; just painted

them in so that I can then make them do their job. And I'm going to ease them in with lighter, brighter

colors of the pot, the crock itself—lighter and lighter on the light side is what I do to further

develop the appearance of my subject. And conversely, darker and darker on the dark side, I not only

improve the texture of the object, but I also accentuate the object's dimension. I use sable brushes to

do this stage because you're painting paint onto paint, so you don't want too much resistance. And now,

this is already dark; I'm going to go darker to show that little hole where the handle wire is fitting

in—darker there. And if I were not showing you how I go about this, I would wait for this pot to be dry

before I'd actually put this handle in. But if I want the appearance of the picture to be, as they call,

loose, I wouldn't wait for it to dry. I’d flip it in with just a few simple strokes. Sometimes that's

kind of the charm of the picture, the rhythm of application in which it was painted—casually rather than

carefully—depends on how much time you have and the mood you're in. But I like to say I don't know

whether you know what I mean when I say it trifle with trifles; pay attention to structure, which is

more important. Oops! That was dumb; I took away the plane of the top, trying to put a feeling of a

funny little cork in there. It's at this point that I would inspect the turning edge and add a

reflection if I wanted it. That means a little lighter tone in the shadow; that's optional. I made it

reddish because of the redness of the composition here. Now let's go on to the finishing of the glass

bottle. You can see that I have it in, but it doesn't look as though it has a front. The front is going

to happen because of the highlights—white with a touch of green's complement, red. And these are going

to hit my brush loaded. See, I'm going to pop one here in for the concave, out for the convex, in for

the concave. I'm going to skip along here because I don't see it until this concavity and this convexity

ease it in up at the top. Again, that highlight seems to dissipate into a brighter version of the color

of the glass itself on the side away from the light. And I see some very lovely reflections. They can

never be as light as the highlight. No tone value on a subject can be lighter than the highlight.

Highlight means the highest light. And now if I slide green over this, the liquid will come become in

back of the glass. The grapes—just as I add lighter light to bring out the dimension of the crock, which

is non-reflective, grapes are also non-reflective. I'm going to make them come out by adding lighter

to—I see this one lighter, see this one lighter, that one lighter; this one is extraordinarily light

right here, cutting right into that dark shape. And these cut in light against the table tone; these

have to remain kind of dark because they silhouette against the bottle. So far from tone values that

somewhat contrast each other, I then make them more contrasting—more light to the light and more dark to

the dark. Then the picture is consistently painted in the same manner, which ties it together. Do you

know that a mistake is just a funny—just a place that's different? It can be beautiful. I can—if I paint

one grape magnificently, I have to do them all that way. But if I suggest each one to be grapes, then

I'll be able to get away with recording the whole bunch. I have a philosophy that backs me up in my

painting to keep me free and keep me from losing my mind. And that is that if I make it all wrong, it's

all right. Using the same procedure on everything does give it a unity, a harmony of mistakes or a

harmony of success, depending on the luck you had that day. It would be so nice to have more time to

show you some of these things. But a demonstration shows the reliable painting principles that I use.

When I do have more, it’s about going darker and darker, lighter and lighter, and they start to come

forward. How about some strategic highlights on those too? Here, here, here, here—don’t highlight all of

them, just the ones that you know are in direct line with the light. These highlights vary according to

where they are on each one; they’re not in the middle, they vary according to the particular view of the

grape that you have. I need a darker tone here to make that grape come forward, so why don’t I sacrifice

it and put it in again? The apple needs a highlight to make it shine. Here’s another basic painting

procedure that I use: I put something on in one direction to make the apple look as though it does this,

and influence it opposite from that way. Now, why don’t we just rest a minute before we develop these in

the same fashion that I did that section of the composition? I’d like to show you how I mix my colors.

In this case, for the highlight on that apple, I pick up white since I’m adding a lighter value and I

plop it down on my palette. Already my brush is not loaded quite right, so I wipe it off. Wiping it off

doesn’t contaminate the color that I’m going into, and I’m going to go into a little touch of violet. I

move it here and then mix it together very quickly. Now the brush is loaded incorrectly again; I have to

wipe it again so that I can take this and pick it up on the end of my brush. Then, I come over to the

canvas, aim it to where the highlight is, and stroke it on. Yes, I put more than I want, so I can ease

it in. Putting that highlight on without easing it in makes it look as though you had a chicken with a

highlight foot walk across the canvas. If a highlight looks like just a piece of paint, it’s not a

successful highlight. If the highlight makes the object look as though it shines, it is a successful

highlight. This is the time that you do have a chance to diddle around, and if once you’ve done it it

doesn’t look right, take it off and do it again. Now, I’m automatically thinking I could darken this

little shadow here; that could help. Now onto the copper pot. You’ll notice that I have the copper pot:

highlight, body tone, body shadow. Now I’d like to put in the tone value that happens with metals, and

that is the reflection. I see a lovely pinkish one here and here, sliding up in here because this is

where it’s catching light from the light tablecloth. That is also happening on this underplane because

the light can—it’s in line with that underplane. As bright as I have the highlight looking now, I’d like

to move that highlight area down a little bit. I can still go lighter if I do what I said I did before:

I take a lot of white, move it down onto the palette, wipe my brush, and put the color into it: orange

and red. I’m going to quickly mix—not mix it a lot, just a quick vibrant mix. Wipe the brush, pick that

vibrant mixture up on the brush, come over to the canvas, and lay lighter color right in the center of

the already existing highlight. Don’t ever be afraid to paint shiny things too shiny; you can always

tarnish it by blending the highlight in. This, of course, has a handle too. Just make some structures as

to where it’s going to go before you connect them. This apple now looks dark in relation to how light I

made the copper pot, so it has to be lightened. I feel as though again I’ll take white, find a place,

and mix red in—that's too red, too orange now. I’m going to move that paint over to the apple. Oh yes,

that makes the illumination consistent. A highlight that didn’t work because I didn’t clean my brush

from red to highlight. A little can be done to this complicated area in here, but I could lighten the

color of the lemon right there, or I could what I call “rhythmatize” strokes to show the texture here

too. This goes down—yes—and I actually see a shine happening. Try to do each stage as nicely as possible

because a picture that has to have a lot of corrections starts to look overworked, and it suffers from

its overwork. Now when we look at this whole picture more broadly, you can see that I have a lot of

contrasts that come as a result of the light coming from the left. Also, the light is coming not only

from the left but from above, thus the table plane has to be lighter to be consistent with the lighting

on the subject. So with a big gob of white and a little bit of yellow, let the light slap the top plane,

the flat plane, and put it on in a way that is suggested by the folds. The basic value that I started

out with becomes the little shadows of the folds. You notice I’m starting all the lighter tones on the

table at the subject matter, not down here, not away from the composition. I want these things to evolve

from the subject. One mark down here just becomes something out of the focal area; it has to be

connected. I think I could stand a little bit more light over there—maybe a little bit more light over

there. Juice the paint, wet the brush a little bit just to ease that action down. Much of what I’ve done

on this picture is repetitious because I did use the same techniques throughout. Let’s review: I start

from the top down, usually make a light side and a dark side on all non-reflective objects—the jug, the

apples, and the grapes. For reflective objects, I let the highlight do the demanding work of showing its

dimension. I cut one shape down with the next shape so that the image seems to grow under my brush. Yes,

there are lots of things I could do to this, like put this little thing in here and maybe soften some

things and lighten some things. For instance, I might want this handle to be a little darker to make it

show up more and accentuate its cast shadow. I don’t like the way this little pot is encountering the

apple, but you could at this point tickle it to death. About two hours have passed; I hope it has been

as interesting for you as it has been for me. They say that a professional is someone who knows when to

stop. I really have no place to go anymore. I’ve used my army of tones, all the lights and darks, and

I’ve recorded all the shapes. The only thing I have left to do is to say thank you for watching—or maybe

I’ll teach you how to make soup! Whoops! Should have my easel more sturdy. That’s too light; I seem to

be running out of my black. Let me replace some.