When you paint white on white, the challenge isn’t finding color—it’s finding value and temperature.

Pure white has no meaning until you surround it with something just a touch darker or warmer.

Look closely: one white may lean toward yellow, another toward blue. Those differences are what make

the light feel alive. If everything is painted with tube white, you lose form and it goes

chalky.

Keep the brush moving across the form, letting one note melt into another. Reserve the purest white

for the single highest highlight, and you’ll see how the whole setup begins to glow.

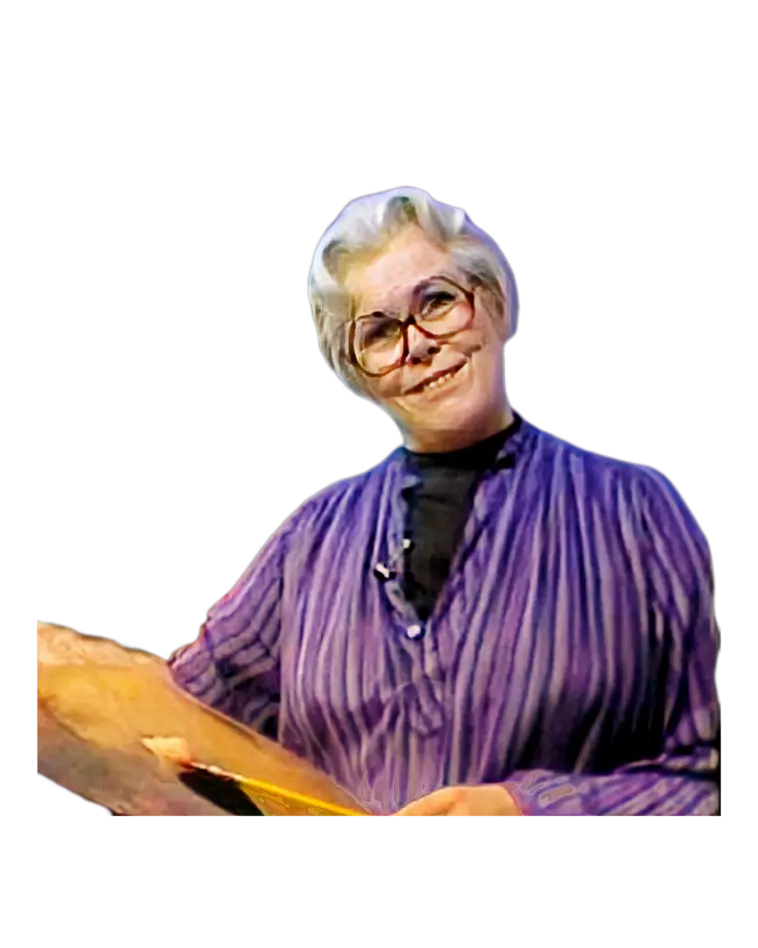

Hello, I'm Helen Van Wyk, and welcome to my studio. Today we're going to examine, carefully, the color

white. Isn't it interesting how we'll talk about shades of blue—dark blue, light blue—shades of

red—bright red or light pastel pink—and yet we never think of light white and dark white? We feel as

though white is white. I've been fascinated with the color white and compositions of white things for a

long time. I like the fact that it is starkly silhouetted against this dark background, and then the

light is streaming across this cloth. I have set up something much more subtle for you to watch today.

I've put a light background, a white table, and eggshells, and an old white pitcher. Let me show you how

I go about presenting white that seemingly has no contrast, seemingly has no interest, but trying to

apply paint in such a way that it takes on a charm. So let me place the subject. First, that's going to

be the rightmost side of the eggshell. This down here is going to be the little bottom of the middle

eggshell, and this is going to be the completed egg over here. And so it's within this area that I'm

going to work quickly, but as accurately as possible, to sketch in that eggshell that tells me where the

bottom of the picture is. I hope that while I show you all about white, I can talk, too, a little bit

about what happens to the beautiful shape—a circle—when it is seen in perspective, and we end up having

to draw one of the most difficult shapes, and that is the ellipse, the perspective distortion of a

circle. I find it's easier to do the ellipse and then add any little addition to it, rather than do the

whole thing. And now this eggshell is here. Remember I said I wanted it to sit there? Yes, and I respect

that because this establishes the composition, which is an asset to the drawing. It's terrible to draw

in the wrong place—not in the wrong place, but in a place that is not advantageous to the pictorial

presentation. And so this gives me a start. I've just noticed, in looking at this, I don't like this one

here. I want it further down. Yes, of course, I'm starting with dark marks. I want to know where I'm

going to put my white paint. I did tone the canvas down to gray so that I can really present the white

onto it. Why don't I start right out with the white pitcher? What color white is it? When you paint

white, you can't paint it just plain white because it's too colorless, and I actually see a coloration

about that. What kind of white is it? I'm going to start out with some white, and why don't I try it...

ooh, that looks darker than that because I will eventually want to put a highlight on it. So I'm going

to put some black in it, and oddly enough, I think it looks a green-white. Always ask yourself some

questions about the color that you're looking at. Ask yourself what tone is it, what particular

peculiarity is the color. This is a very light gray, vague green. Painting white is an excellent color

lesson. Well, actually, if you can paint one color beautifully, you just have to apply that knowledge

and that sensitivity to all the other colors you see. And now I'm going to put the shadow in, in the

complementary color to green—violet—very quickly presenting the general overall tonal and color effects.

I'll go back to that, and the reliable wonderful cast shadow. What an odd shape that cast shadow is in

this kind of lighting. I'm going to change it and make it my own shape. We don't paint what we see; we

paint what we saw. I saw a better cast shadow another day. Now with the light coming from the right, I

have to make believe I see this white background darker over here because I can't paint white against

white or light against light. I always have to put light against dark to make the image appear on the

flat surface. The handle—oh, sure, that'll come later. Now the table is a warm white. A warm color is

any yellow, orange, or red, so I yellow ochre into the white to present this. Section of paint

presentation of the subject. Use violet, too, for the cast shadow. I want to do this very quickly

because I have something so much fun to do on these eggshells and cover the canvas with eggshell color.

Well, they're light, they're yellowish, and not much of a color, just a dab; they even look a little

green. One way that you can learn to see the variations of white is to put a raw egg next to a

hardboiled egg, and you'll see two different textures, two different whites. I'm going to step back.

Before I do, I'd like to wipe away a little bit. Why? So I don't have to be bumping into all this wet

stuff. It'll be just a little soft asset to the next things that I'm going to do. Why don't I start

really working on the background to show you how to arrange your tone values to be able to put a white

subject against a white background? I've just painted this with a greenish gray; now I'm going to darken

that with its complement, violet. And yes, away goes the pot, because I want to do that better, and now

a darker tone again. Now, yes, this seems to be adding color, but when it all gets on the canvas, the

orchestration or the harmony will present a colorful white, because we do always want to show our colors

off as lovely as possible. This is a lesson that I have used in my teaching life for years and years.

They say, "Oh, if you have studied with Helen Van Wyk, she's going to make you paint white on white, and

she's going to make you paint eggshells." This is the shadow. Isn't it nice that the dark over here is

balancing this shadow? And there's a little example of my blending technique that I call "poopsy-do."

And that prepares the area for me to do this ellipse, so white—remember, I made it a greenish white

again. Now the darker background is now making it possible for the light of the thickness of the pitcher

to show. Arrange your contrasts. Let's take a hypothetical situation: what if I had that white pitcher

with lights all the way around it—back, front, top, side? Would you be able to see it? I don't think so.

It would just disappear in glaring illumination. We never see in nature that kind of lighting. We live

in a world with one source of light—the sun—and that's why I arrange my subject matters in that natural

situation and study what it does to the subjects. What it does to the subjects, it shows them off so

realistically. Now right under that ellipse, there's a darker tone, and under that, there's a lighter

tone because of the little ridge. And with a bigger brush, I can come down with this off-white. In this

particular case, the off-white is gray, greenish white. That color is not that difficult to recognize;

it's the shadow color that's a little bit tougher. But we rely on nature; nature tells us you always

have to use the complementary color, and so I've mixed a gray-violet to send that color into shadow. I

want to hop now—hop to doing the eggshells. Let me step back a minute, though, so I can think a little.

I always think things out before I start to paint. I'm going to try to have you sit on the end of my

brush, sit right here so you can watch. In order to have you sit there, I have to knock the devil off

that sits there all the time saying, "Helen, I bet you can't do it. I bet you can't do it." So now with

yellowish white, I'm going to paint that back side of that egg. Put it down and then coat it again,

feather or release the pressure of the brush as you encounter the shadow, and now darken that color with

gray to help that color roll into shadow. And now use violet, its complement, way over here on the dark

side of the palette. Yes, I do see the shadow on that egg, that dark. That's what's going to make it

look dimensional, what's going to make it look real. It's in a very light situation, and so my

reflection is going to be quite light, and that fills in the shadow, and then the egg stands on its own

with its cast shadow. This egg is casting a shadow; the shell is casting a shadow on the back egg, which

I need. I need that dark. Now I have a very fragile little shape to make—the thickness of an eggshell,

the thickness of its shell. My goodness, yes, there. And I'm going to cut it down with the shadow. The

interior, the inside of the eggshell, is a different white than the outside. It looks yellowish, and I

want this shell to come in front of its back shape, so why don't I slide that further down? Oh yes, if I

made this yellowish orange, to add some yellowish orange in the shadow too—reflected light, reflected

color—move this all the way down. This is a very studious manipulation, but something that is well

learned on eggs and more easily applied on shapes that are not as fragile as this. Doing a painting of

eggshells is like practicing, like the musician practicing scales. Practice. Don't always be painting

pictures that you are inspired to paint; paint pictures just because you love to paint, you love to try.

Now I can cut that eggshell up, blend in the edge, and now always the last tone value is the

reflection—that's that lighter tone you see in the shadow. It's not what you paint; it's how you paint

it. A brush that has a nice sharp end makes this difficult paint maneuver a little easier. Now, how

about that eggshell? Paint versions of them here by painting in the contrasts caused by the lighting.

Let me step back, see what I did. Since I paint what the light does, the light has to be consistent, and

so you can see how there's the same type of light hitting the bowl as is hitting the cloth. But if you

look at my picture, I have one kind of light hitting the eggshells, and the rest of the picture doesn’t

have the same kind of illumination. So I use my eggshells as a key to then relay all the other light

areas or white areas to it. So now this is going to get much lighter. I won’t have to worry really about

losing their appearance because I have the tone values arranged, or nature has arranged the tone values

for me, so that rarely am I going to have light against light—I’m always going to have light against

dark. Here I have the light table against the dark cast shadow under the pitcher. Here I have the light

forming the cast shadow. Oh yeah, here I'm going to have a problem; I'll think about that later. So now

I have white subjects on a white table. I have to whiten the background—it looks like a green

background. When painting white things, use a lot of color in the beginning so that you can use pretty

much plain white—pure white—into the color to make the presentation you had in the first place. That

way, you're painting all whites, but your brush is always dipping or blending into the color

presentation you set down in the first place. It’s a good idea always to start your pictures with a lot

of color. That amount of color will withstand all the diddling you're going to do with it to finally end

up with the effect that you want. And of course, this pitcher doesn’t have as white a look—look how the

green is veering its greenish head because I’ve made so much of a white type of presentation with the

background and the foreground. A little bit of alizarin crimson into the white to put the shine on it—a

highlight, a highlight, a highlight. And here they stand out too much. I could lighten the whole picture

utilizing the green, the tone I started with, as its fuser color or blender color. Oh, the light is

sitting right in that concave shape of its spout. Yes, I'd like to make the shadow side of the vase

separate itself from the cast shadow from the vase, and that again—just as I used a reflected light in

this egg, I’m going to use a reflected light in the pitcher. The reliable five tone values—learn them on

white, apply them to other colors. I have a highlight, a body tone, a body shadow, a cast shadow, and a

reflection. Next time I meet with you, these five tone values, these five reliable tone values, will be

used to paint drapery. They are really quite omnipotent. So, next time I will paint drapery—or maybe

I'll just make soup.