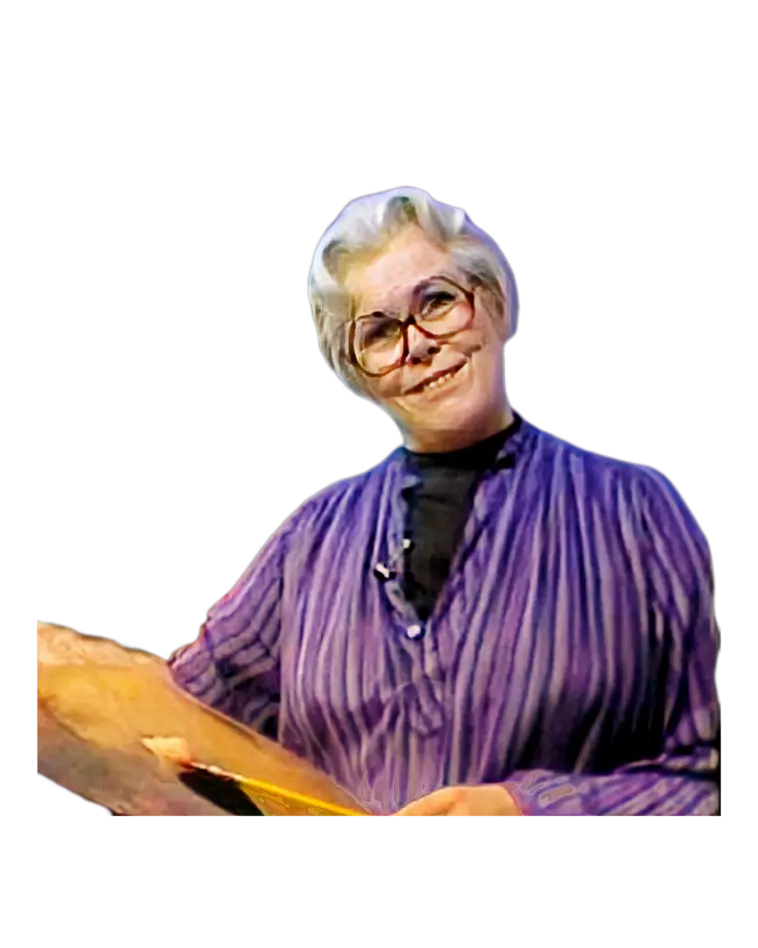

Hello, I'm Helen Van Wyk, and welcome to my studio. Yes, I'm talking today about efficiency.

Efficiency really needs planning. You ever notice how someone seems to do something so well when

it's being done? But that doesn't mean that the person hadn't thought out the whole project ahead of

time. So let me, um, show you. How I plan out doing eyes. Let's look at these eyes. This is Jesse,

and this is Bonita, such a sweet, wonderful woman. Look at the eye sockets of Jesse—they're kind of

deep. And look at Bonita's—they're wide apart and so open and endorsing. So I've sketched on this,

uh, board, if you can see. I've sketched in the basic shape of Jesse's sockets, which is the first

thing you should aim for in an efficient way to paint one of the most difficult or complicated

features of the face. So, with a gray, I usually start out by indicating the overall eye socket,

going back to what her skeleton looks like. And then the eye socket is against the nose. Yes,

there's lots of things within that eye area that are not dark, but it really is so much better to

start the eye in a dark tone to begin with. Why? Well, let me show you why. You always have to ask

me why, or I leave you in the dark. The forehead—if we look at the side view of a face—here is the

forehead coming. It's a plane where the light strikes. Then the eyes are here, and then the nose

comes out. So light can hit the forehead, light can hit the nose, but the light can't hit on these

planes here and here. And then, of course, the mouth is again another example of light and dark. And

that's why it's better to start the, uh, eyes as an overall shape of dark. The under plane of

Jesse's nose is also dark, and of course, it casts a shadow. The longer you make that cast shadow,

the more her nose sticks out. Now let me show you the change or the difference in the mass tone of

Bonita's eyes. Her eyebrows are flatter. The eyes—then I always like to do this shape and this shape

together. I never do that whole shape and then this whole shape. Doing it this way and this way, and

this way and this way, helps you keep them in perspective and helps you make them a matching pair.

And then just wash in—this is the beginning stage of everybody's eyes—just wash in the overall shape

of the socket, and that takes in from the eyebrow to the last bag. Let me show you the difference

between these two. You'll see them better if I take out this mess over here. Of course, these shapes

are blended into the rest of your tones, so there's two types of sockets, and that is the beginning

of the eye's likeness. Let's take another factor of eyes, and that is that inside this socket,

there's a ball, and in that ball, there's an iris. And the iris is glasslike, just like this. So if

we know how to paint a glass ball, we'll be able to paint the iris of eyes. So let me do this

eye—this ball to represent a blue iris. So, um, we don't see the whole iris—the lid always covers

half of it. But I'm going to—just because it's going to be fun to do this for you—I'm going to do

the whole iris and fill it in its general overall tone. Now, there's something about reflective

types of textures—reflective, they're shiny—and that's what makes them have an obvious, a very

obvious highlight. If the light is coming from the right, the highlight would be then here. Now,

because the eye is glasslike, that color or the light striking here goes in and bounces out there,

or shows up a lot right there. And I think that just by doing that, you can almost see that this is

starting to look a little bit more transparent. It's going to look extremely much more transparent

if I darken it over here on the side where the light comes from because it's right at this point

that the light is not affecting the glass at all. It only can fill in the light over this way. And

so that's the kind of knowledge that will help you paint the iris of an eye. So let me put that

understanding into practice here. Here is the iris—now that's that lower part—and it sits in a

non-reflective ball. But it too has its way of getting light and dark. This gets the darkest on the

light side, but a non-reflective object gets a shadow on the dark side. So we only see the real

white of the eye over here. So this looks a little bit more like a round ball and is held into the

basic eye socket with a lid and held in on the bottom with a lid. Now, the eyelid casts a shadow

over the iris and the ball. There's always a little membrane there. This particular dark that's

right under this thickness of the lower lid is a legitimate tone. Legitimate in that I mean you

should paint that in. It's the next one and the next one that you shouldn't put in. Couldn't resist,

couldn't resist that, because it's that—this particular one is structural. That's the one that makes

it look as though— And now inside the iris, we have the pupil, and we want to make this blue part

look glasslike. I think I have to make a few little indications of what I'm—what these are—examples,

demonstrations, diagrams to point out how an understanding can help your aim. Yeah, that's better.

So now we have here—I put a highlight. That highlight usually hits right at the corner between the

pupil and the iris, right about there. And then the color of the eye, meaning this, is diagonally

across from it in line with the light. Now, because an eye dilates, it's best to paint that in in

strokes to be like so. That's when you really, really do put the color of the eyes. Some people have

such dark eyes you can't even see that, but it's a good thing to put something about it in to help

that look like the texture of glass. So you add your knowledge to what you see to make your picture

extremely convincing. And now this is where the eye gets darker—that represents this. So there's the

evil eye. It's all well and good to understand the elements of an eye, the socket, and the ball in

the socket, but how do you ease this information into actually painting an eye? You see, I did this,

and this is important—the socket shape, and this is important to know—but this is not in context to

the actual painting of a person. And so I would like to show you how I use that understanding in

painting these eyes. I painted her eyes out just for you so that you could see the progression, the

efficient progression of application to include all the elements that her eyes are. So you can see

that I started out—I painted them out by putting in the shape of her sockets, and I do that with a

color that is rather neutral—not the color of flesh and not the color of shadow, but gray, just a

gray. Sometimes a little bit warmer than a warm gray. How do you make a warm gray? Black, white, and

a warm color. And then, before I start working on the eye itself, I have to take my colors of the

surrounding areas and move them up to their shapes and then start to work into the eye itself. So

now I have the socket in a general tone. Now I'm going to find where the light hits. Well, let's

always look at things from the top down. The light is coming, in this case, from the left, and this

fullness catches light, the shape of which, of course, is extraordinarily important. Now then,

there's a corresponding shape over here, but it's a little different than this because the eyes are

at different perspectives. So we just see maybe a little bit of light there. Each addition of shape

into this socket adds to the likeness, so it's up to you to try to be accurate about the shapes. Now

load your brush at the end—always load the brush at the end—because that's the part that does all

the dirty work, or the good work. Now, the light can hit the thickness of the lid and how the lid

meets the side plane of the nose, but not there, because that's in cast shadow from the nose. Then,

as you look, you see that the light can strike the eye on this side and the eyeball on this side,

but not on the other side because it's a ball, and that's the shadow side. And then the eye is held

in with the lower lid, and this is a very important tone, value, and shape right there. If you move

that way up, she gets mean-looking. Move it way down, she looks kind of starry-eyed and innocent.

And I told you about that legitimate dark shape under that lid—that's what holds the eye in. Be kind

about all the other ones, the ones that start to drip and drag down from the eye. But we always see

this a little lighter. Why? Because it's a highlight area; it's a concave plane. Now, that's the

light that I see in the eyes. And now, where are the darker darks? We're just letting this basic

tone act as the general overall dark now. So now the darker darks are shadows—violet or green, a

gray cool color. I took black, white, and Alizarin Crimson. Let's see how this looks. Yes, that

seems to enjoy the colors it needs. And this is the shadow from the eyelid on the eyeball. And then

there's a shadow here in that crease. Many people disconnect the iris from that shadow. It should be

done—it should be all together in one tone to begin with. It helps. You don't put the color of the

eye in now—the iris—that's just what. If you put that color in and your aim was kind of bad, it's

better to just put it in a darker tone and push the color into it. Now for the pupil—black. Yes, I

use black, but I never use it alone. I take black, and I'm going to put her pupil in with black and

blue. Why black and blue? Because her eyes are going to be brown, and that black would be a bluish

color, complementary to the brownness or orangeness of her eyes. And so I put that in. My brush goes

back to my palette a lot, and very quickly, because I always have to be working with a loaded

brush—constantly have to correct. Let me go back to this lower lid—better. Don't ever make the white

of the eye pure white. Put a little bit more white into your flesh color. See, I have the flesh

color here—I've just added white into it so it has some life. We always see a nice highlight, light,

or lighter tone here too, so now I can put that highlight in. You can't put the highlight in until

you have done all that I've already done. And then, remember on the blue ball, the light made a

highlight and then bounced out across from it. Now, she has brown eyes, so white, orange, burnt

sienna maybe. And this is where you actually see the color of the eye and the glass-like quality of

the eye. I try, when I give these lessons to you, to not, um, confuse you with correction, but it is

very tempting because when I do the eyes, I never do the eyes without seeing the same tone values on

the rest of the face. To make these tone values enjoy this entire presentation—because that's what

painting is—it's a presentation of a likeness, not really a likeness. So let me step back a minute.

Now, an efficient way of looking is to work from the top down, because you don't miss anything that

way. So let's see how that top-down way of looking gives you a chance to put in every element of the

eye. Starting with the brow, after you've put the socket in, of course, is to then accentuate the

eyebrow, because that's one of the things you have to take into consideration. And then the shape

that's right under the eyebrow. And by working from the top down, the top of the brush corrects the

bottom of the shape that you last did, and then the bottom of that shape is corrected with the next

shape you put in, and then that is corrected with the next one. Just watching the top of the brush—I

love to work this way. And then the iris, and then that's corrected with the lower lid. You've seen

me—many of you who have watched my program before see that I always do this—I always work from the

top down. Don't think that you have to be different with everything that you paint—a different

technique. One reliable technique for everything. I think that, um, the pianist uses the same

fingering for each scale that he has to do. And so then, darker, to put this in now. "E" in painting

stands for effort—sometimes it stands for excellent if you're lucky. Next time we meet, I'm going to

tell you all about, um, what comes after "E." "F"—yes, one of my favorite subjects—or I'll teach you

how to make soup. Hello, I'm Helen Van Wyk, and welcome to my studio.