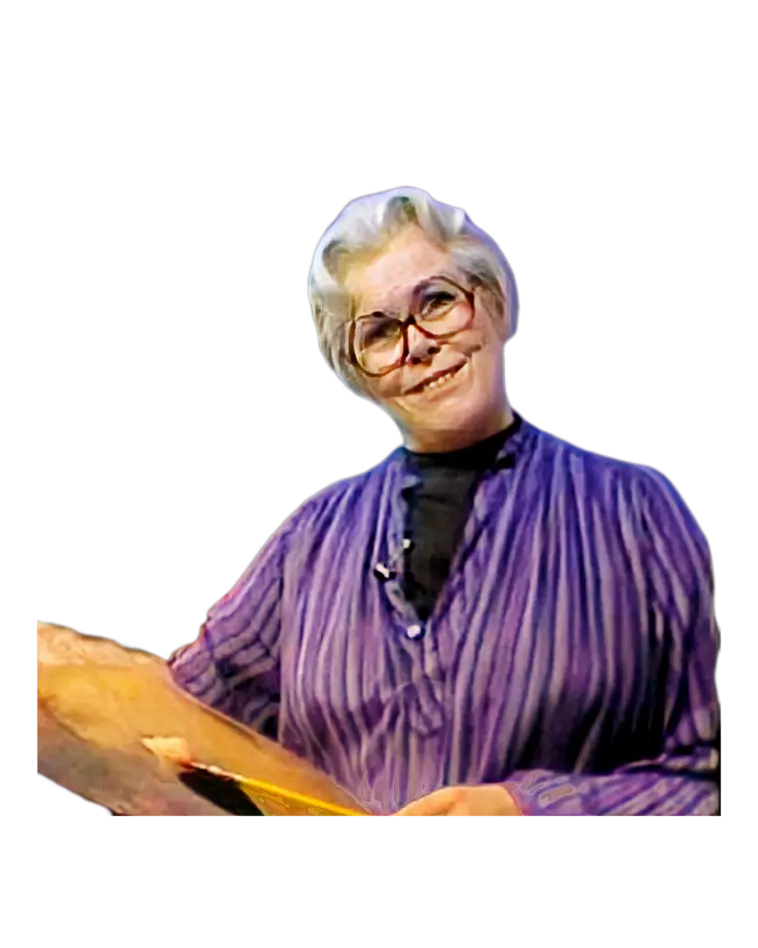

Hello, I'm Helen Van Wyk and welcome to my studio. Today's lesson is all about foreshortening. Yes,

something that we have to become aware of because it is an element of perspective, seeing things in

the way they are at that particular time, not the way we know them. The way we know them becomes a

preconceived idea, and very often that invades the way we really can see. I would like to show you

something. Look, which one looks bigger to you? The one on the right? But look, they're exactly the

same size. The reason this one looks bigger to you than this one is that you're comparing this shape

to this shape, not to the one that's further away from it. This painting with books flopped down on

the table looks quite successful. This one does look flopped down; all these look flopped down, and

in actuality, it is this shape dropped. So, I've set up a number of books so that I can show you the

factor that will help you see things in perspective or make things look as though they're being

foreshortened again and place the subjects so I can make them all fit. That's about as simple as the

over outer outline is. And remember, quite a while ago, I said I usually start with just blobs.

That's going to be the red book, by the way. I think one time in one of my previous sessions, I told

you about the wonderful rag lady. She sends me these little rags that I rely on so well. Now, she

sent me a little book because she thought it was just a wonderful little book to paint, and it—I

think it is too. It's just a nice proportion and a nice color. So, that's just the composition. Now,

let's really try to flop these two books down on the table, so they are foreshortened. What's

happened is there's a great change in the proportion from top to bottom in relation to side to side.

I'm going to measure from the top page; compare it. I'm going to make this proportion from here to

the bottom of the green book and compare that distance to the length distance. And would you believe

that from here to here has to be twice this, twice that? So that's what happens when things are set

in a position that is not like we remember them or know them. Their proportion changes greatly. So,

I have to fit in this flattened thing two books that we know are more up-and-down shapes. Proportion

becomes the best friend of foreshortening. Now, the Little Red Book that the rag lady sent me, yes,

I know how wide it is, but now I don't see it very wide. I see it rather skinny; it's only

become—oh, it's only that thin. This one is a relief. This happens to be a book in a position that

is very recognizable, and this is equal to this, and it's up-and-down. I did that just to re-give

you an example of our preconceived idea of a book shape in relation to what happens to them when

they are set in peculiar positions. And again, here's another one that's not an ordinary book shape.

That's the brush I want. Let's start with the shadows now that I have indicated their drawing and

position. There's a shadow here, there's a shadow here, this page is in shadow, this book is casting

a shadow, and all of the books are on a dark table. Most of these sessions that we have together are

wonderful exercises. I'm getting a lot of practice. Try books; they're not difficult shapes once you

recognize that the books are presenting one particular problem, the problem of foreshortening,

because we don't have to arc anything or make that many—we don't even have to make a turning point,

just masses of geometric shapes. Coverage, and it looks like I have the problem of what color is

off-white? White with off in it? This page is a yellower type of white. Ooh, I'm not learning my

lessons. I made this back book too light. You can't get it right until you get it wrong. Just find

out how wrong it is. I think I haven't told you or reminded you of my philosophy that makes me keep

my sanity: I make it all wrong; it's all right. Or I start with a mistake and see how wrong it is,

and then see how wrong, and then try to correct it. There, that's going to make that show up. Now,

this is not a rectangle. It's more— well, it's not as long as that book, really, as I know it to be.

It's shorter, and this shape is the parallelogram, not a rectangle, and this is in shadow. The

little brown book had that a long time; that's a very old book, and its light gold pages. I think

it's a book of Psalms or hymns or something. I haven't read it lately. Even though it has gold

pages, the gold pages are now dark, because that's also a preconceived idea. We have preconceived

ideas about color too. We think gold is always light. No, gold can be in shadow and be very, very

dark. Thank you, rag lady. What a nice color that book is. I call her—she signs her—when she sends

me these rags, she just says, "From your wonderful rag lady." Now, the down plane of this book, the

pages drop down more in shadow, drop down. Remember when I was—if any of you watched me paint the

wave—I used opposite strokes, one direction, another direction, to give character to each element of

the object's anatomy. Now I've just gone down; that almost dictates to me to go across with the red

cover. Once you've established the proportion, proportions of the shapes that you see in

perspective, you have almost 50% of the object shape in your control. As I paint this, I'm reminded

to remind you to always work with a loaded brush. It's terrible to get the shape the way you want it

and then say, "Oh, the paint isn't— it isn't covered enough," and then have to go back. Going back

sometimes messes it up a bit. And now, let me step back and see if I have given the illusion that

these are flopped down, foreshortened, and I've did this up-and-down so that you could see the

extreme variation. Foreshortening not only affects books, but you have to think that foreshortening

is a problem almost in every subject that you paint. For instance, painting a portrait: now you see

my face coming right at you, this side is the same as this. As soon as I turn my face, there's a

foreshortening. This has gotten smaller than this. Hands, oh, are such a problem to paint. Remember

Rosco saying to me, "Helen, hands are so difficult." Two, or too many. So, we have the problem of

turning the hand in. Look at how it looks this way and how it looks this way. How many other

instances? We can't ignore foreshortening. So, I've awakened you to it as a factor in painting. But

now, let's just finish this picture. I'm going to have you help me do it. Before I actually do the

background, I'd like you to decide what color background you would want. I'll keep my mixture

secret, so you think out what color you think would be an artistic choice, one that is befitting

maybe a library, books, or this general overall composition. Well, I'm going to use library green.

What did you come up with? Don't they paint a lot of libraries green? But I think the green that I

used is also a way of bringing this green color up into the general overall color composition of the

picture. The choice of background. So many people say, "How do you decide on the color of the

background, Helen?" I say, "Well, sometimes I use the process of elimination, decide what colors I

don't think would look right, and then end up with the only one that's left. I wouldn't use blue, it

would dominate too much because it's so different from all the rest. I wouldn't use red, surely. And

I wouldn't use brown, it would rob this. And I can't make it gray; there's too much off-white or

off-gray in the picture already. But I do think I'd like to make this book stand out a little bit

more, so I have to change the table color. While I try for a table color, why don't you think of

one? Well, you're going to ask yourself three questions. Or, ask yourself not three questions,

you're going to ask yourself: Is it going to be yellow, orange, or red? Violet, blue, blue or green?

Certainly aren't going to call it table color because you don't have table color. Most tables are in

the orange family. That's too much like that. Well, but that's the color I want, so how can I fix

it? I'll change this color and make it more—a little bit more intense, so I can use this less

intense lighter color for the table. Always make sure that the colors you use enjoy each other as

they sit together side by side forever on your canvas. I'd like to lighten that there. I don't like

the way the table color came and met the background color. My picture, I could do with it what I

want. And green with some red in it to help the shadow from this book on the background. That book

is of the drawings by the students of the Art Students League back in 1942. I went to the Art

Students League a little later than '42. It was a good place to go. Spent a lot of time at an easel

there. When you write—I'm not going to—I'll put some writing on that. I'll be discreet. Don't write

word for word, just make paragraphs. It would make an interesting picture if it was that particular

book with those illustrations. Now, I can sharpen. I can add—wouldn't you like to see some light

shining in here? Maybe a little different color? A flat plane. Repair the edges. Brighten the light

side. This looks like an empty hole. Whenever a shadow looks that way, don't take it away, just add

some warm color in it. Black, white, and yellow ochre, maybe. Soften the edge. This book is how to

learn Italian. Herb and I go to Italy a lot for the art there. That catches a lot of light because,

my goodness, it's right in line with the light. And here's another example: see how that shadow

looks better and this one looks empty? You make them gray first to see where they are, and colorize

them later with some warmth. We have a bit of a trompe-l'oeil type of thing happening. This book is

jumping out over this; isn't that nice? This has to be darker. There's a nice shadow coming from

this book, the green book that's flopped down on the—that, because it's lifted up. And also, there's

a shadow here from the red book on the green book. Oh, here again, I have two tones that are too

much the same, helping the foreshortening with light and dark. I want that to go back, I want this

to be forward. I'll lighten it. I need more contrast here, constantly searching for more contrast.

Now, to write on the books and to title all these books, I should let all this dry. So, I see a nice

little flash of light on that book, and I'd like to neaten up that edge. Oh yes, there's lots of

things I could do, but time is out. And next time we meet, I'm going to paint a portrait of a lovely

girl. Or maybe I'll teach you how to make soup. Hello, I'm Helen Van Wyk, and welcome to my

studio.