Composition begins with placement. Before you commit to details, decide what the picture is

about and give it room to speak. Try the subject higher or lower; a half-inch can change

everything. Don’t let the main shape touch the frame in a way that confuses the eye.

Think in big masses. Where is the visual weight? If it sits on the left, give it a counter-shape on

the right or more air to balance. We’re designing movement for the viewer, not decorating empty

space.

Whether it’s a portrait, a landscape, or a still life, settle the placement at the start. After that,

drawing and paint handling are easy— because the picture already knows where it’s going.

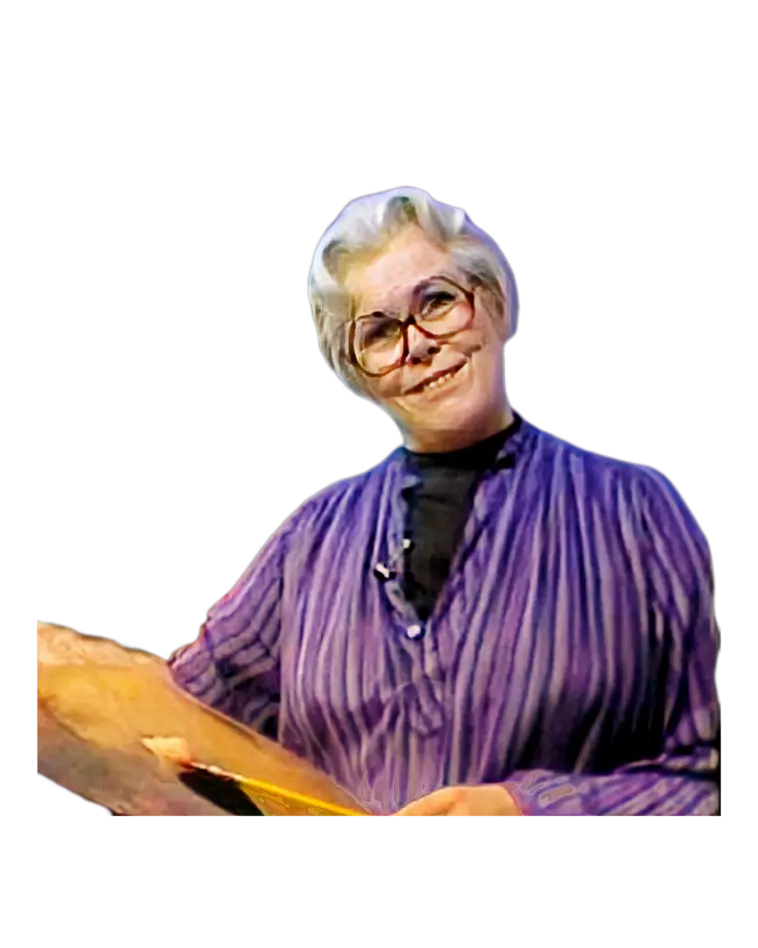

Hello, I'm Helen Van Wyk, and welcome to my studio. Today's lesson is about placement—the seed of good

composition. I'm going to do a portrait, a landscape, and a still life—just the placement stage. So, let

me start with a portrait, and may I introduce you to Herb, my model husband, and show you a portrait

that I did of him a number of years ago. You may think that when I begin, I think in terms of his eyes,

nose, and mouth, but I really don't. I start very simply, just by the placement. Let me show you how I

do it. I have a canvas that's 30x40, the same size as this portrait. Herb is posing for me, and I have

to think in terms of situating him nicely on this surface. What if I started his head here, thinking of

the drawing of his face? Would I have enough room for his hands? I doubt it. Uh, if I started there, got

a very nice drawing, and then came down here and didn't have enough room, I'd say, "Well, maybe I didn't

want the hands anyway." But I do, because I was really inspired by the portrait that Sargent did of his

teacher. I thought the portrait composition was stunning, and it was a good way to study portraiture. I

always like to study with the best of them, and Sargent was one of the best portrait painters that we

had. So, how to begin is always the first problem. I want to include his head all the way down to his

hands, and so I'm going to make a mark and say, "That's about the optimum amount of space I want to

leave between the edge of the canvas and the top of his head." It is not his chin that I would do next

because I still don't know whether I'd have enough room to include his hand arrangement. So, I'm going

to make a mark down here somewhere that's going to indicate where the lowest finger of his left hand is,

and it would be somewhere through here. Now, I would like to make a mark on either side to make sure

that he's centrally located. I don't want him to be too much to one side or the other, so I think that I

would make a mark here to say, "This is as close to the edge as I want his left arm," and the elbow over

here. Now, I have an envelope. I call it an envelope. It is within this area that I can now concentrate

on the drawing—not quite yet. Drawing is so much a matter of proportion, so why don't I just make a few

connecting lines to see if this overall shape kind of wraps him up. Yes, and so now I know that I've

respected the size of the canvas. What if I had a very tiny canvas? I could do the same thing; I’d just

have to reduce it all down to fit into that size. So, the size of the canvas is always your

consideration, and how big you're going to make it and how much you want to include. Now, this has

helped me to begin the drawing problem. How much of from here to here is his head? I can measure it.

From the top of his head to his chin at my arm's length is this much. I've seen people do this and then

go here, and they say, "Oh no, it couldn't possibly be that." No, that's not the way to do it. Top of

the brush at the top of the head, my thumb at his chin, and I'm going to see how many heads go into from

here to his hand—one, two, to the buttons, three, to the end of the jacket, and four, almost four to his

fingertip. So I can divide this into, well, one, two, three, four. So, this is going to be his head

size, this is going to be the buttons, this is going to be the end of the jacket, and this is going to

be where his hand is. To carry on, still thinking in terms of the organization of the entire subject on

the canvas—not how fascinating he looks at this point—I’m going to see how much is to the left and how

much is to the right, kind of dividing him in half. Starting with, let's say, his nose. From his nose

over to the left side of his body—is that bigger or smaller than from his nose to the right side? It's

smaller. In fact, from the center of his face from6 here to here equals his shoulder. Let me see if I

can get that in. Everything is now being geared according to the size of the head. So, my mind is not on

drawing; it's on placing the big elements. Maybe I could take a chance—always take a chance. This is

going to be where his head is going to be. I'm not seeing it any more than the space that it's taking

up. The other larger element is the upper part of his torso, and I like to relegate the shapes into

simple ovals. That's his arm, his forearm; this is the other part of his arm and his hand. And this arm

down this way, the other part of his arm, and his hand. Oh yes, it's so difficult, but I kind of go by

saying I can only think of one thing and do one thing successfully. I can't think of two things and do

two things successfully, so I have to relegate this to the simplest of beginnings. And then, I know

where the buttons were, and so now I have where the collar is, and then simplifying his jacket into

saying, well, it's double-breasted, so I have two lines of buttons. And, he looks big on this. One of

the things about painting is that you... you have to do it and judge it. You don't have a way of knowing

how it's going to look before you do it; you have to do it and see how it works. And so now that I have,

I know it's going to fit. I know I'm including all that I had in mind. Now I can start putting the

drawing within that overall... the overall marks, and start zeroing in on how much is his hair, where

his eyes are, where his nose is, of course, his mustache, and so on. Always looking where I've been, not

where I'm going—because where I've been tells me where to go. If I have his chin here, I know that then

his collar is down from it, and then this is going to go to the... the buttons in through here, and so

on. So, I wanted to show you how I initiate a portrait, and it's always starting the shape, respecting

the size of the canvas. I don’t... it's very tempting to continue on with this picture, but I think I've

shown you enough to say that don't start your pictures by drawing it. Start your picture by placing the

subject so that you can put the drawing within the security of the placement. So let me step back, and

I'll set up something else and show you how I can use the same technique on another subject. I just set

this canvas up to recreate how I began this still life using the same technique that I used when I

sketched in Herb's portrait. Painting is not that easy, but any difficult job can be accomplished if you

dissect it into two stages: simple steps. It's like walking a trip of a thousand miles; it's a step at a

time. So, let me employ the same technique that I used before and show you how I did this painting. I

have the subject similarly set up over here and, again, always respecting the outer edges so that the

subject doesn't spill out or get too small. Get it the way you want it. We make marks. Maybe you're

wondering what I make my marks with. I like to use turpentine and ivory black to make a definite

statement. Some people like to use a lighter type of tone, but I feel as though if I'm going to make a

mistake, I might as well make a bold one. So, that's going to be the top of the bottle, and this is

going to be the side of the blue milk bottle down here. All the fruit or vegetables are going to land

somewhere around in here. The last little slice of cucumber is going to be on the upper rightmost side,

and then the little white pitcher. Surely, with these secure lines, looking at the entirety, you can say

how much each of these items take up. Well, maybe a suggestion for the blue milk can, and then the

suggestion for the bottle, and then a suggestion for the lettuce, the cucumber, and the other. You see,

these marks don't really exhaust you. You don't fall in love with what you've done, and you're apt to

juggle them more. Oh, here is where all these lemons, all cut up, are going to be, and they talk to you.

They tell you whether you've composed the picture nicely, that it looks as though nothing is making the

canvas tip too much to one side or too much to the other. Because in composition, we do like to see the

canvas well-balanced. Also, it tells you that you have variety: this size is not the same as this size,

is not the same as this size. Many different sizes spread variety on the subject, and so we have balance

and variety—two of the elements of good composition. Then, within this, you can see a little bit more

about the structure—not the exact drawing, but just the structure. These are all cylinders or three

cylinders, and the bottle. Also, this is a time that you can decide whether you want to alter the

proportions. I don't like the size of that lettuce; it's a little bit too big. So, it's my poetic

license to make it the size I want it. So, don't just paint what you see; paint what you want. Setting

down a placement on the canvas can lead you to more artistic wants because, after all, that's what you

want to add into your picture—not just to do it, but to do it artistically. Something that looks

naturally lovely because it is nature that is rather lovely. There's nothing wrong with nature; we can't

fool with Mother Nature. We just want to make our artistic comment on it. One of the things about nature

is that nature is in balance, and nature has a magnificent variety and unity about it. So, you can see

that by starting with some simple marks, you can make some judgments about each of the elements. If you

start, let's say, what if I started this by just doing the bottle and making it big again? I would then

maybe spill out of the canvas when I really didn't want to. So here it is: a simple beginning used on

how to do a still life. Oh, but now I want to show you how to place a landscape, and this system doesn't

work. You have to alter this system because outdoors you're just so overwhelmed with everything. So, let

me take this canvas down and get a canvas so that I can show you how I go about seating a composition in

landscape. Now we're faced with the problem of composition in the great outdoors. This is a painting I

did in Gloucester a number of weeks ago. When you go outdoors, you look at a spot and you see something

fascinating, and that is your focal point. In painting outdoors, you start with your focal point and

extend out—just the opposite of the way you do a still life or do a portrait. How can you envelop the

whole world? And so, right here, I think you'll notice is what you look at first. We never put the focal

point in the middle, and it's always a little offside. It's down here toward the left-hand corner. Let

me show you how I go about doing a landscape and see the composition in seeing a subject and parking it

on the limits of a canvas. Right there is my focal point. I always kind of say it starts, and then it

has to ooze out. From here, I begin and then act accordingly so that the rest of the subject, the rest

of the canvas, supports the drama of the focal point. Now, with black and white and some umber, the tree

and how much it takes up. Sometimes, because outdoors you have the sun moving constantly, you have to be

as quick as possible—expedited as easily as possible. Washing the dark pattern in with a cloth is easier

than trying to wash it in with a brush. Sometimes when you have a brush in your hand, it can do so many

wonderful things. You start to see the details rather than the general overall appearance that you

should start with because you really should always have the simplest of beginnings. Let me do this

painting for you. And so, with a little bit more strength of drawing, now that I know where the tree is

going to be, I'm going to say, yes, that's the trunk, and then I have another branch that goes off to

the left. It's sinking in. This is one of the things I liked about it. I saw it, and it led over to the

right, and so I left more space over to the right. It was almost automatic that I felt the focal point

should be on this side because I did enjoy the fact that, as I saw the tree, I did see the fence in

relation to it and the rocks. By the way, this is a version of something that's right down the street

from our house. The only thing I did is I eliminated the house. That's the wonderful thing about being a

painter; your picture—you can do anything you want with it. Sometimes eliminating is wiser than

including more. Edit what you see, simplify it, and get good strong patterns. Well, as many of you know

who have seen me before, when painting anything, you have to have a place to start. Since we're trying

for the depth dimension way in the back and then come forward, it almost seems practical to start with

that which is furthest away, and that would be the sky: a cobalt blue and white. Yes, I can tell you

what colors I dip into, but I can't tell you the proportion exactly, meaning how much white and how much

blue. This is something you have to decide by actually putting the color down. I always say the best way

to get the right color is to put the wrong one down first. See how wrong it is? Then you can always fix

it because you're always addressing your picture to how it looks to you. So, that can be the beginning

of this. By now, the next element seems to be those trees off in the distance. Look, instead of a new

mixture, I'm going to get the tree mixture right out of the sky mixture. That will help me get maybe a

feeling of atmosphere because, in painting outdoors, that's one of the things you have to take into

consideration—the fact that these green trees are the same tone or the same kind of greenery as the tree

in the foreground, but they're much lighter because there's more air between me and these trees. When

painting distant trees, try to again employ a little bit of what I spoke about when I was showing you

the placement and composition of still life. Try to make that shape have variety—not all exactly the

same, as though it looks like a whole bunch of lollipops all in a row. You may think that it's just the

fact that I'm rushing a little bit so that you can see how I do this—that I overlap. But I overlap all

the time so that these colors can meet. Then, there's a road—yellow ochre and white in this particular

situation. Many of these elements that you see in a landscape have to be translated into brushwork:

things that are up and down are painted up and down; things that lay flat sometimes are recorded better

in horizontal strokes. Now the fence, where it up, can be horizontal strokes. I mean vertical strokes. I

try, when I paint outdoors, to limit my painting session to two hours because in two hours the sun

remains somewhat the same; all the contrasts are kind of similar. Because here, on this day, the sun was

hitting the tops of this stone wall, and the sun was hitting the tops of these stones. As the day goes

on, the whole composition changes because composition is so much a matter of beautiful patterns of light

and dark. And of course, back now that the canvas is all ready for it, I can put the tree back, and this

is a cast shadow from the tree in the foreground. So putting in the overall composition, starting from

the focal point and seeing how you can relate the rest of it to it is the way I begin a landscape. I

don't do it quite as roughly as this, but I do do it rather broadly so that I can go back and then work

into all these areas. For instance, I would go back and work into the sky now that I know where the sky

is. Again, starting at the focal point, starting at the tree, making sure that my sky is most active and

excitingly colored in the interior of the picture. I would never just make a big light thing over here;

it might distract. So everything emanates from the focal area. It's a good idea when you're painting to

constantly step back and see how things are going. You can see that I did spend quite a bit of time

developing this focal area. I put sky holes in and made sure that the light was flashing behind this

tree, making sure that I had a nice silhouette of this dark tree against the lighter tree and then this

grass that comes up in front of it. So I spend my time developing the focal point. I've taken the

painting that I was working from and put it on my easel, and even though it was more advanced than the

one I was showing you because it, after all, only diagrammed what this important factor of painting is,

which is the placement and the beginning. I can see that I would, even on this, try to focus the eye

more on the focal point by livening up the sky right around here, maybe being a little bit more accurate

about these little sky holes, making sure that the interest stays right in through here. This maybe,

this could be brightened. Oh yes, that helps a lot. And so I hope that you've gained some insight and

maybe less fear about beginning a picture. Next time when we meet, I'm going to tell you all about how

dimensionality breeds reality, or maybe I'll just teach you how to make soup.