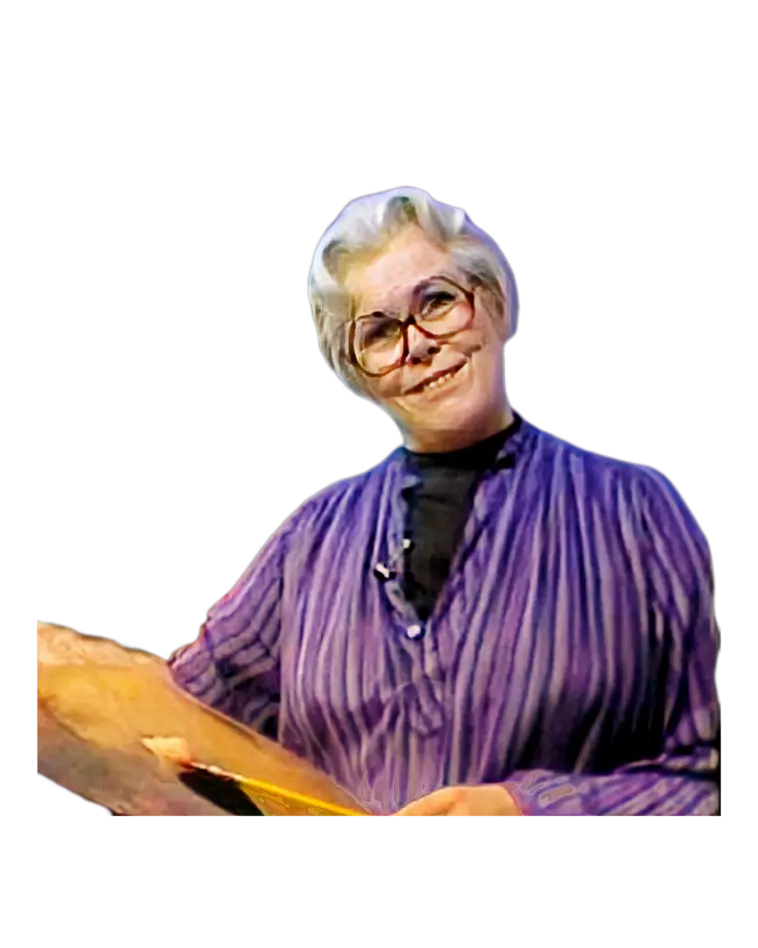

Hello, I'm Helen Van Wyk, and welcome to a new series of "Welcome to My Studio." This series is going

to deal in threes, and today's lesson is going to demonstrate how paintings are done one, two,

three—a one, two, three approach: a beginning, a middle, and an end. Symphonies are done in threes,

three movements—one, two, three. Plays are very often done in three acts—one, two, three. And as

with them, painting too is the second act, or the second movement, or the second step. So let me

begin with number one first and show you how one, two, three can really work. Those who know me are

familiar with the ever-present toned canvas. I don't want to work on a white canvas; it makes

painting too difficult. Painting is difficult, you have to make it easy. So one of the ways to make

it easy is to tone the canvas in a way that is sympathetic to the subject that you want to do. I

want to do white flowers; I want to end up with white flowers, so why start with white? So I've

started with something that is less than that. Step one is always the planning and the placement and

the proportioning to make sure that I get it to fit. So why don't I start out and make some lines to

indicate where I'm going to end up? I don't want to start in the middle, I may end up off the

canvas, so I like to make a limitation of the subject matter on the canvas and not think that much

about the drawing, but the arrangement.

This always seems to be a frightening time of the picture. I like this stage the best because you

have so many possibilities about it. Your expectations are high; everything seems to be so much in

an embryonic stage that you're not intimidated by what you've done. I'm not anyway because I'm not

really too worried about how this is going to turn out. I want it to, I want to do my best, that's

all, just my best. I think you're watching me, you worry more about how it's going to look in the

end, and I worry about how this particular stage is looking. And it seems like a good seed—a seed of

a painting, not a painting. Heavens, it takes long to get a painting done, but this first part of

stage one is the beginning of a nice play. So there's already another third or three happening on

this canvas, which I'll talk about in great length some other time. The focal point is right about

here, and that's at the third mark, and so I have dropped my interest right here—not in the middle,

not over here—right at the third and hope that the interest kind of blossoms out from it. So after

the placement—that was really proportioning and placement—now I have to make a little bit more of an

indication of the drawing, the drawing of each flower, not in all its petals, but in its direction

and perspective. Some people like to spend a great deal of time doing every little bit of the

flower, every little nuance of every little petal at this particular time. Yes, if you want to do it

that way, fine. But when you paint flowers, you have to be a little bit more aware of the time

because they're not going to stay alive forever. Of course, I'm not in jeopardy today because these

are artificial. It's all right to practice from artificial flowers. The real ones do sing out and

give you a much nicer message, but these do happen to be quite nice...peonies? Peonies, I don't

know, how do you say that? So they all fit, it all seems to work here. And the vase that you see is

not the vase I want to use. It doesn't seem to— I wanted to squat it down a little bit more, and so

I'm going to make up my own vase. And that represents in very quick order the three parts of step

one: the placement, the proportioning, and the drawing. Now I can get on to that very important step

two, and that is the development of the beginning. I've already captured your interest with act one,

now I have to work and have you understand what act one is all about.

So let's start out with what stage two in the one, two, three painting approach is, and that is I'm

going to lay in paint over this whole canvas wherever I need paint, and it is all over. So all I

have to do is apply the tone and color of the paint in the areas that I've indicated. You'll be able

to see, by starting on a darkened canvas, that I can start with the white flowers now. I don't make

them pure white; I have them dirty—dirty white. I dirtied them with black and yellow ochre to make a

warm gray and try to have my brush suggest the outer silhouette. You can't make a brush draw a line,

but you can make a brush fill in an area. Ooh, that's a little bit too dirty. Don't worry about that

black paint getting into your mass tone. It might be dulling it a little, but remember this is only

the second stage of this picture's development. The colors are not the colors that you actually see,

they're the foundation colors for what you actually see. And if they are a little bit duller and a

little less brilliant, they're a far better fertile bed for the flower's actual appearance. You've

heard me say so many times before, you can only get three things wrong: the shape, the tone, and the

color. There's a three for you. So I've just put in a suggestion of the shapes, which I can improve

by putting in the background with their contrasting tone right out of the puddle that I did the

flowers with. I mix my new tone for the background. Why not use up that paint that I already had?

It's not going to hurt it. And also, when you know you're going to do a big area, mix a lot of

paint. Don't be a little puny about it. And so often I have seen people who have not had instruction

do a background, and they start doing this, they start covering it the way they would paint a wall.

But that's not really what the background is being done for. The background is being done to aid the

pictorial content of the picture, and that means that you should really start around the flowers to

help have the background shape the flowers, keeping in mind that you want to have this first lay-in

of the background suggest the overall look of each bloom. It's at this time that the picture could

look poster-like, not with any feeling of intrigue, mood, or even depth—just flat. But it's a time

that something has to be done because, after all, you're making a painting, and there's an old

saying: you're never really painting until you're painting into paint. So at this time, don't ask

anything more of yourself than to cover the canvas with the tones of the subject and try to maintain

a feeling or the spirit of the object's shape. If you think of one thing at a time, you're in more

control of what you're doing. One thing at a time—just cover the canvas and shape the flowers.

People say, "Oh, Helen, you paint so fast! How can you be doing that so fast?" I say, "I'm doing

very little. All I'm doing is covering the canvas. That's what I've got my mind on." If I had my

mind on how wonderful I thought those flowers have to be, I would be so frightened. It's when you

are intimidated by the end result that you are afraid to do what you're doing. And every product

goes through a funny stage. Just think of a cake—a beautiful cake, beautifully iced and decorated.

At one time in its life, it just was a bowl of glob that had to be well mixed with good ingredients.

And so that's what I'm doing now. This is comparable to mixing the batter. It's so funny how so many

people approach other jobs with common sense and yet approach a painting trying to use some other

kind of attribute, thinking that it's made of magic. It isn't. And yes, my greenery is all darker.

I'm using sap green and burnt umber—add white in it for where it's lighter. And let's put this

darker green in here to suggest the greenery. Be consistent about your stages. I would never start

again working on the flowers and doing anything more to the flowers while ignoring the vase and the

table, because the vase and the table are just as much part of this overall picture as the flowers

are. You can't really say that you're working, you're doing flowers; you're painting a picture of

flowers. So, just for fun, I think I'm going to make the vase blue, see what blue will do. I need a

relief of color. Ooo, wow. People say, "How do you choose your color?" I say, "Well, try it out, try

it out first, see how it looks." That just looks too bright to me. I think that would be more

workable for me at this stage. And so I don't get too many colors in here, I think I'll just put the

table to a kind of a white cloth. Ooo, I'm going to have to stop a minute and put in some more

white. This is getting too dirty. But it's a good idea to put your surrounding areas, the negative

spaces, in a duller color first. You can always brighten it up later. Whenever I put in this dirty

color on a tablecloth, I think of my first mother-in-law. She was so clean, and it just delights me

that I'm painting in something so dirty. She used to come into my house and look for all the cobwebs

and see if her dear precious son was living in a clean environment. I'll dirty it up even more

because I see a cast shadow there. Now I want to step back and see what this lay-in of the basic

tones looks like, because this is only the beginning of step two. It is not the completion of step

two. I will not go on to step three until I feel that I have worked this out to a certain degree,

which I hope to show you when I come back to it. This is the most important part of the picture

process—this in-between stage, this modeling stage. It's time that you have paint on the canvas, and

you can start moving it in a way to get a little bit closer to the appearance of the subject. And

it's pushing the paint out over the background or moving the background color into the shape. This

is the stage that takes the longest. This is the stage that people like to rush through because they

are so anxious to get to the end and have it look exactly like the subject. I much rather stay at

this correctable stage—the stage where I can still move the paint in the shapes that I think are

going to set the final look. This is that wonderful mud pie stage. So many little soft qualities of

tone and color happen at this time. And it's also at this time that you could, if you wanted to,

start introducing the colors that you ignored the first time around. It's at a very correctable

condition. It's never a correctable condition when you have painted the image in the beginning the

way it looks in the end. You have to keep your stages right—what happens in the beginning of the

picture, what happens in the middle. And it's all that the beginning and the middle are done for the

sake of what you can finally do. And when you finally do it, well, then the affair is over, so you

want to get at least something out of it. So it's back and forth between the negative space and the

positive space, or the flowers and their background—not how the brush can, but as to the pressure I

use to give either a found or a lost edge. I'm really trying to keep the edges as fuzzy as possible

at this time. Of course, I'm looking for light and dark always—where the flower is toward the light

and where the flower is away from the light. Many people think that this is a process done

differently when I'm in my studio. No, I do it the same way; I just take a little longer, and I'm

much more careful. So you can see they begin to feel a little bit like peonies. Now I'm going to go

to step three, finishing it. I would never get to this stage, or this step, until I really felt that

I enjoyed the picture as it is—that it was a suggestion of all that I had aspired it to be. So then

I could just continue it and finish it off. And I think I'd start right in by pleasing my first

mother-in-law, who's up in heaven cleaning the place, I know, by lightening the table, especially

around the vase. I don't have the time to finish everything because it just is impossible, but I can

demonstrate how to finish it. You'll notice that this is still quite flat. There is an amalgamation

of color because I've fused the negative with the positive. So now I can put it into focus and

finish it by inspecting the subject matter carefully and finding out where the light is striking the

petals the hardest. The light is coming from the right, so any petal in line with that light is

going to be lighter. Now you can see how beneficial that second stage is. If you try to get to the

second stage too soon, you don't really have the essence of the flower embedded in your painting.

This addition of the lighter tones—this stage is just as important as step two, and it takes long. I

would probably work on this picture for two hours adding the lights, but let me step back a minute.

Yes, I've been working on this picture, this demonstration of one, two, three. You see, I'm

finalizing with some lighter tones to show the stems and the leaves, and I would certainly suffer

over the vase a little bit more. Please realize that my lessons to you demonstrate what can be done.

But I do have something here of almost the same subject that I took longer to do. You see, a little

bit more time makes a different effect. So next time we meet, I'll teach you another one, two,

three—or here it comes—I may teach you how to make soup. Hi, my name is Helen Van Wyk, and welcome

to my studio.